Issue 5, Lughnasa 2018

Áine Uí Shé, A Champion for Irish Dance, 1945-2018 · McKiernan Clan gathers to share golden memories · Recognizing the Irishness of the fantasy genius Lord Dunsany · Support CJAC’s ‘Mural in the Midway’ · Tale One: The Legend of Billy in the Bowl

Introduction to the Celtic Junction Arts Review, Lughnasa 2018

Welcome to our first year’s anniversary edition. While the wheel of the year has whirled past since August 2017, our online quarterly cultural magazine has successfully fulfilled its mission of providing an archival record of the bustling artistic energy field housed in the Celtic Junction Arts Center. As we begin our second year of quarterly editions, we find ourselves intermingling loss and regret with commemoration and celebration. The theme of preserving and honoring the memory of those who burned with passion to assert Irish cultural identity poignantly saturates this edition’s articles.

Cormac O Sé provides a comprehensive and heartfelt account of the achievements of his mother, Áine Uí Shé, a moving force in the global story of Irish dance, who sadly passed away in 2018. She championed Irish dance for 47 years since founding with her husband Séamus a dance school in Dublin in 1971. Cormac followed in the family tradition by founding O’Shea Irish Dance in Minnesota in 2005.

Nick Coleman also sadly left us in 2018, but he contributed an archival article from the Pioneer Press in 1988 celebrating the Golden anniversary of the great Irish-American cultural bridge-builder, Eoin McKiernan and his wife, Jeannette. We, in turn, are honored in this edition to commemorate the highly talented Irish-American journalist and polemicist, Nick Coleman even as he commemorated the achievements of the McKiernans thirty years ago.

My article argues that despite Lord Dunsany’s political differences as an Anglo-Irish Unionist with the moving forces behind the Irish Literary Revival, W. B. Yeats and Lady Gregory, he deserves to be recognized as one of the Revival’s canonical figures and a genius in the field of innovative fantasy and speculative fiction who was proud of his Irish roots in county Meath.

Carillon RoseMeadows gives a brisk account of the stellar artistry of Marty Ochs and Carrie Finnigan. They are creating a stunning new mural that is steadily taking shape and forever transforming the brick edifice of the Celtic Junction and enriching the experience of driving along Prior Avenue.

I conclude the edition with a fantasy tale mingling contemporary Dublin/Minnesota characters with the harsh world of eighteenth century Dublin. It is the opening tale in a longer work of Young Adult fiction: The Map-Maker’s Tales.

Dr. Patrick O’Donnell, Editor/contributing writer, is a full-time English faculty member at Normandale Community College. He is the founder/director of the Saint Paul Irish Arts Week (since 2016), Cultural Area coordinator for the Irish Fair of Minnesota, and Director of Education for the Celtic Junction Arts Center where he also teaches Irish literature, literary history, and mythology. He recently co-edited the anthology The Harp and the Loon: Literary Bridges between Ireland and Minnesota.

Áine Uí Shé, A Champion for Irish Dance, 1945-2018

O’Shea Irish Dance (OID) is the longest tenant of Celtic Junction, and was very much the catalyst for finding and opening the building in 2009. Most folks know that OID was born in Minnesota as an immigrant company in 2005 under the directorship of Cormac Ó Sé, T.G.R.G. with his wife Natalie Nugent O’Shea, but they may not know it comes with a long history that winds deeply through both Ireland and America. OID is the continuation of a long-standing tradition of Irish step dancing directly out of Dublin Ireland. It was there that Cormac’s parents, Áine and Séamus O’Sé, produced a 47-year strong school with thousands of students and world-record results as Scoil Rince Uí Shé. While their legacy continues, the end of an era arrived when Áine passed away this June at the age of 72 due to brain cancer. The effect she has had on dance in Minnesota, in Ireland, in the broader United States and across the world is astounding, and little known outside of the Irish dancing world.

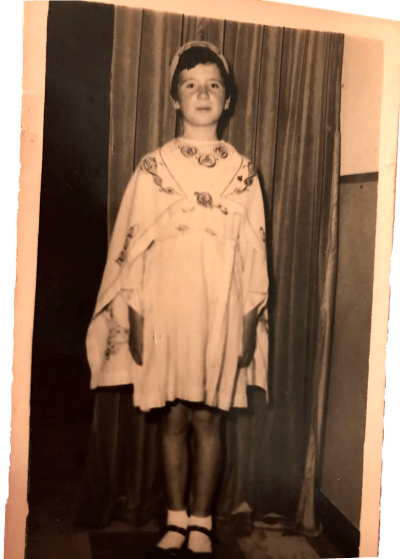

Growing up in Crumlin, Dublin in the 1950’s, Áine was fascinated by dance from a young age, and learned the basics in school from Rita Walker English, her teacher. Áine attended lessons with the late Charlie Malone for a number of years. For her father, dancing was not a priority. Bartholomew Walsh was a 6’2” policeman (yes, the Garda Síochána were required to be over six feet to serve) and he, in particular, was not one for frivolity. Áine colluded with her mother, May Walsh, to sneak off to dance lessons. She loved it, and thrived in her abilities and skills – but with the strict rules of the household could not possibly get a dancing costume. Her mother would carefully press the pleats into her simple school skirt and blouse, then bleach and wash her white ankle socks, drying them by the fire to be ready for morning. Even after all her years of dancing, Áine never really had a dancing dress of her own but instead wore a costume borrowed from her aunt Eileen who was also an Irish dancer.

The absence of a costume of her own never dampened her love or spirit for her craft, and she continued pursuing both step and ceili dancing. At age 14, Áine took over the running of a club for girls in a branch of the Gaelic League (Conradh na Gaeilge) where girls could take part in activities including dancing through the medium of the Irish language. Áine met her future husband, Séamus Ó Sé, at an all night Scoraiacht (hooley) in Rathmines, Dublin. The night they met, they literally danced all night and went straight from the Saturday night ceili to Sunday early morning mass at 5am. They were inseparable from that point on and married in 1968.

In the mid 1960’s, they had become regulars in the Irish version of “American Bandstand” for RTE’s production of Club Ceili. Every week, a live band would play and the cameras would roll, showing off Dublin’s hot, young set in their High Caul Cap or Walls of Limerick.

Áine and Séamus opened a dance school in 1971 as their daughter, Dara Ní Shé, turned two and was soon going to be ready for her first steps. In time, an order of fine orange wool was procured, and a seamstress found and the first Scoil Rince Uí Shé costume was born. A tiny, hand-embroidered costume was made in preparation of Dara’s first competition.

In the late 1970’s, Áine and Séamus joined the Folk Dance and Song Society of Ireland. From then on, they embarked on taking young dancers and musicians, often a group of thirty to forty, on busses, ferries, plane and trains across to the mainland of Europe and Scandinavia. For the following twenty years, they danced and played music at Folk Festivals across Europe such as Hartberg Austria, Concarneau, Confolens & L’Orient in France, Minturno Italy, Skelleftea Sweden, Zelhem Holland, Kaustinen Finland, Pacs Hungary, and even next door to Sidmouth, England.

In the mid 1980’s, their school, busy during the year, would quiet down in summer and Áine and Séamus would whisk themselves and their children off to North America to do Irish dance workshops across the continent. Dancers from New York to California attributed their steps and technique to the O’Sheas rolling through Winnipeg, Chicago, Syracuse, Ohio, San Diego, and more.

In the early 1990’s, their dancers performed professionally for tour groups, for private organizations in such places as Trinity College for its 400 anniversary, Dublinia Viking museum and the famous K club Golf resort. The O’Shea troupe danced professional shows multiple nights a week in front of thousands of people.

Forward a few years to 1994, and for the 25th anniversary of the World Irish Dancing Championships, Áine’s son, Colm, won his eleventh and final world championship title, more than any Irish dancer before or since. In spring of that same year, Aine and Séamus’s culmination of success came with the appearance of 17 of their dancers in RTE’s production of ‘Riverdance’ as the interval act of the Eurovision Song Contest. Riverdance The Show took off the following spring with its heart-pounding rhythms and soulful melodies catching the attention of the world. The show employed over twenty of their top level dancers including their own three children Dara, Colm and Cormac. Over the subsequent months, Áine and Seamus found themselves rebuilding their championship class and rebuild they did.

Áine and Seamus didn’t rest or have any inclination to be idle, they both traveled the world, visiting their own children and dancers wherever Riverdance would take them. As adjudicators of Irish dance, they continued to judge championships from Ireland to the UK, America to Australia and New Zealand. As part of An Coimisiún le Rinci Gaelacha, the world body of Irish Dance, Seamus became Chairperson in 1998, holding the position for ten years. Encapsulating their own global vision, Seamus became the first chair to oversee the World Championships shared outside the home country to Glasgow, Scotland and on to Philadelphia, in the United States, making it a world-reaching event and growing it tenfold.

With hard work and perseverance, their own dance school also grew again, and 1998 in Williamsburg, Scoil Rince Uí Shé performed a summer show at Busch Gardens, Virginia. Áine and Seamus along with their daughter Dara were asked to create a full show in 2001 titled “Irish Thunder”, and the park created a whole segment of their theme park around Ireland. For five years, the show packed out 8 shows per day in a 900 seat theater with dancers from their own school. In 2004 their show expanded to Busch Gardens in Tampa, Florida.

Following the huge success of Irish Thunder, Áine, Seamus and Dara were commissioned to create a brand new show entitled “Emerald Beat” which was performed in both Busch Gardens parks for the following four years ending in 2009.

In the meantime, their son Cormac had moved to Minneapolis Minnesota in 2001 and founded O’Shea Irish Dance. Áine and Seamus still made time for their own grandchildren beginning with Adrienne’s first steps of a baby reel on a visit to their class in Navan, Ireland. They came to Minnesota with Dara for workshops with Cormac’s dancers, made visits to support them at National and World Championships. Scoil Rince Uí Shé and O’Shea Irish Dance competed against each other in the Senior Mixed Ceili at the World Championships in London 2014. They became the first parent/child schools to place in the same competition on a world stage, holding 3rd and 6th places, respectively.

Over its 47 year history, Scoil Rince Uí Shé achieved over 30 Solo World Championship titles, and numerous Ceili and Figure Choreography World Championship titles along with dozens of All Ireland, All Scotland and Great Britain titles. One of their cherished accolades is being awarded the overall teachers cup for Feis Atha Chliath (Dublin Feis) for 28 consecutive years. Áine and Séamus were the Honorees of the 2017 World Championships, recognizing their life-long commitment as champions for Irish Dance.

Áine worked so tirelessly for her love of Irish dance, she attended the 2018 world championships this past April, and even chaired her final meeting of the Music and Dance Committee at a meeting of An Coimisiun in May, travelling from her hospice bed to do so. From there, Áine was still planning to attend a dancer’s wedding and she hoped to travel to the North American Irish Dance Championships in Florida in July as well as having the opportunity to drive again. There was no part of her that wanted to rest or to give up her passion. Her family didn’t want to give her up either. The extended O’Shea clan is deeply appreciative for the heartfelt condolences and lovely remembrances they have received following her loss.

Áine is remembered by An Coimisiún Le Rincí Gaelacha, the Irish Dancing Commission in Dublin, for her contribution to its mission:

Cara linn ar shlí na fírinne……. Is oth linn a chur in iúl daoibh

Go luath maidin Domhnaigh, cailleadh dlúth chara de chuid An Coimisiún le Rincí Gaelacha, Áine Uí Shé ADCRG, cathaoirleach Coiste Ceoil agus Rince. Go dtuga Dia suaimhneas síoraí dá h-anam uasal Gaelach.

Bean cneasta, croíúil, fuinniúil, dílís agus fial a bhí inti, a bhain go leor amach le rath agus séan. Léirigh Áine cion i gconaí don teanga, don rince agus do chultúr Gaelach ach thar gach ní eile bhí a clann féin mar aon lena ‘clann rince’ lárnach ina saol. Chruthaigh sí atmosféar faoi leith de spraoi agus gáire ag ócáidí rince, thar na blianta. Rinne sí tréan saothar ar son na rincí Gaelacha ar fud an domhain, ina baile ársa féin – Baile Átha Cliath agus sa Ghaeltacht le linn di a bheith ag múineadh in Rann na Feirste. Comhbhrón ó chroí le Séamas, Dara, Colm, Cormac, an clann uilig agus a cairde rince: Is oth linn bhur mbris. Braithimid uainn tú, cheana féin, a Áine ach beidh tú in ár gcuimhne go deo. Slán go fóill, go dtiocfaimid chughat insan mbaile síoraí.

An Coimisiún le Rincí Gaelacha deeply regrets the death of one of our long standing members and chairperson of the Dance and Music Committee, Áine Uí Shé ADCRG: Rest in Peace.

She was a kind, generous, loyal and energetic lady who won much success worldwide for her huge interest and devotion to Irish dancing, the language and the culture in general. Above all else, her own family and her ‘Irish dancing family’ were uppermost in her heart and soul. Great for a gathering of friends to share and laugh and chat she brought a special atmosphere to Irish dancing gatherings the world over. As a teacher, adjudicator and grade examiner she worked tirelessly for her great love Irish dance in her beloved Dublin, in the Donegal Gaeltacht of Rann na Feirste as well as across the globe.

Áine, we miss you already, but we will not forget you. Goodbye until we meet again.

Editor’s Note: The Celtic Junction Arts Center’s Executive Director, Natalie Nugent O’Shea commemorates Nick Coleman and the central donor of the McKiernan Library.

The CJAC McKiernan Library received this article from Nick Coleman this past spring, which was only one of the thousands he had written, of course, but it is special as it relates to our Library namesake, Eoin McKiernan.

Published in the Pioneer Press on January 9th, 1988, this article is a time capsule of 30 years ago, for the McKiernans’ Golden (50th) anniversary. In his article, a sentimental Nick recalls a gentler time of anniversaries and family gatherings — of travel and visions of all the McKiernan children and grandchildren gathered around them in celebration.

Nick gibes and jokes with the family about Eoin and Jeanette “getting hitched” in Brooklyn, comically describes their impressive arrival in St. Paul in Fiat wagon in front of Mickey’s Diner in 1960, and summons ghostly images of Eoin guarding a hole in the kitchen floor from rats with a .22 rifle while preparing “Hamlet” for his class the next morning.

As he signs off, Nick writes “You can’t do justice to 50 years of marriage and a tribe of McKiernans in a newspaper story.” Well, we can’t do justice to either of these great men here either, but we hope it makes the remembering of their paths crossing even more meaningful, and perhaps a little bit sweeter, thirty years later.

–Natalie Nugent O’Shea

McKiernan Clan gathers to share golden memories

by Nick Coleman (Pioneer Press Jan 9, 1988)

Don’t be alarmed if the streets are a little crowded today or if the hotels are all booked. The Shriners aren’t holding another convention. It’s just the McKiernan Clan, gathering in tribute to the man and woman who started it all.

It was 50 years ago Friday that Eoin McKiernan and Jeannette O’Callaghan got hitched in a Brooklyn church and what they have accomplished in the half-century since then would be more than enough for several ordinary lifetimes. But then, there is nothing ordinary about the McKiernans.

You could see that in 1960 on the morning they arrived in Minnesota – two adults, eight children and 300 pounds of luggage all squeezed into a tiny Fiat station wagon that pulled up to Mickey’s Diner in downtown St. Paul after a non-stop trip from New York. St. Paul hasn’t been the same since.

On the surface, Eoin McKiernan was a mild-mannered English professor who had been wooed by Bishop James Shannon to come to St. Paul to head the English Department at the College of St. Thomas. But McKiernan had a vision. He came to St. Paul with a dream of building a bridge between America and Ireland, the country where his parents, as well as his wife’s parents, had been born.

St. Paul was not exactly on the the tip of every Irishman’s tongue when the McKiernan’s rolled into town. But it is today, at least when it comes to Irish artists and authors and educators and musicians, because Eoin McKiernan smooth-talked and cajoled and schemed until he had built something called the Irish American Cultural Institute and turned St. Paul, amazingly enough, into a must-see city on the itinerary of thousands of Irish men and women.

In the years he was president of the IACI, he also inspired thousands of Americans, including many from Minnesota, to visit Ireland and keep alive the connections between the new land and the land of their ancestors. McKiernan, who still serves as chairman of the IACI board, has flown to Ireland so many times that he has spent months at 30,000 feet above the Atlantic.

But that’s the public side of the mild-mannered English professor and his love of things Irish. He and his wife have accomplished much more in their private lives, not the least of which was raising nine kids.

Their names read like a roster of Irish saints. There’s Deirdre (she stayed in New York when her family headed west), Kevin, Brendan, Nuala, Ethna, Fergus, Grania, Gillisa and Liadan.

Today, they are doctors and photographers and college registrars and veterinarians and homemakers and they are spread from New York to Illinois and from Minneapolis to California.

Among them, they have produced 28 grandchildren and they’re all in town today along with in-laws and cousins and other relatives (that’s why the streets seem crowded) to celebrate the Golden Anniversary.

One of the McKiernan daughters, Gillisa, flew in from Africa where she is between stints with the Peace Corps.

The anniversary will be observed today at a 4 p.m. Mass at St. Leo’s Catholic Church in Highland Park, followed by a family dinner at St. Thomas and an evening of storytelling and sentiment at home.

Raising nine productive citizens and caring people is a big accomplishment, but the McKiernans did that while he was teaching English to college students and she was teaching first-graders and he was leading tours of Ireland and she was leading bike trips through France and he was finding volunteers to teach English to Spanish-speaking adults in St. Paul. Then, later, together, they turned Eoin’s vision into the IACI, an internationally renowned organization with thousands of members in 28 different countries.

It makes you want to get up and take life by the horns, doesn’t it?

Kevin McKiernan, the second oldest of the brood, says no matter how busy his parents were, they managed to accomplish not only the necessities but the niceties, as well. Once, Kevin says, his father spent an evening studying “Hamlet,” preparing for the next day’s class, while holding a .22 rifle in his arms and guarding a hole in the kitchen floor where some repair work was being done in case any rats tried to come up into the house.

“Every once in a while, I would peak in from the dining room and there he would be, waiting for the next rat or for the next Hamlet ghost to appear,” Kevin said. “They were always juggling four or five things at a time. But the one thing that was most important to all us kids, the thing that changed our lives, was that they gave us a view of social responsibility to other people. My parents were always reaching out to other areas.”

You can’t do justice to 50 years of marriage and a tribe of McKiernans in a newspaper story, but it says a lot when a family spread across two continents puts everything aside to gather in St. Paul in the depths of January.

When people raise a toast in Ireland, they say “Slainte” – health and long life. I want to say “Slainte” to the McKiernans here and I will say it quick because they don’t sit still for long. Their kids leave town Monday; on Tuesday, Eoin and Jeannette go to Yucatan to see the Mayan ruins.

Recognizing the Irishness of the fantasy genius Lord Dunsany

Patrick O’Donnell

“Dunsany is a man of genius, I think. . . I want to get him into “the movement.” W.B. Yeats in a letter to his father in 1909.

Edward John Moreton Drax Plunkett, 18th Baron of Dunsany

“The care of Dunsany’s reputation currently rests in the hands of the fantasy community, since the Irish critical establishment continues to regard him with a stony silence – whether it is because of his Unionist stance, or his aloofness from the Irish Renaissance, or the occasionally unflattering treatment of the Irish found in some of his work,” state two slightly mystified preeminent American Lovecraft scholars in the “Introduction” to a book recording their ten year quest to assemble a Dunsany bibliography. So vast is the material involving Dunsany’s fifty year career that they insisted their bibliography was merely “preliminary.” What is genuinely surprising is that the brilliantly innovative and pioneering Anglo-Irish fantasy author, poet, essayist, novelist, and playwright, Lord Dunsany (1878-1957), Edward John Moreton Drax Plunkett, 18th Baron Dunsany, of Dunsany Castle in County Meath, Ireland, and Dunstall Priory in Kent, England, is not fully embraced as canonical within the Irish Literary Revival by many Irish scholars and literary historians and his work has been “either scorned or deliberately ignored by those who should have been acknowledging it as a distinctive contribution to the national literature.” This neglect is indefensible as he is unquestionably the most important Irish fantasy writer in terms of influence on British and American fantasy authors across both the twentieth and twenty first centuries, particularly J.R. R. Tolkien, H.P. Lovecraft, Arthur C. Clarke, Ursula K. Le Guin, Neil Gaiman, and George R.R. Martin. Dunsany in all of his complexity needs to be critically recognized as one of Ireland’s great writers and reintegrated specifically into the Irish Literary Revival as one of its innovative geniuses.

Dunsany was born in 1878 in London and passed away in Dublin, Ireland, in 1957. He was subsequently buried in Kent, England. He most fits Michael Davitt’s description of the Anglo-Irish politician, Charles Stewart Parnell: “an Englishman with an Irish heart.” Such a description also encompasses other Anglo-Irish figures like Sir Tyrone Guthrie (1900-1971), founder of the Guthrie Theater in Minnesota whose prominent Anglo identity also saw him largely neglected by Irish scholars. Dunsany was an Anglo-Irish aristocrat (his biographer calls him a “sporting peer”) who arguably takes seven literary pigments (one Jewish, one Greek, one American, two Irish, one British, and one German) and blends them together to create his cosmic wonder tales. First, the Old Testament as presented in the King James Bible provided for him a vivid fund of archetypal imagery and lyrical phrasing; Homer’s Odyssey articulated for him the inspirational vision of the intermingling rivers of myth and fable; Edgar Allan Poe’s American nightmare tales – particularly “The Fall of the House of Usher” – opened numinous imaginative terrain encompassing doomed ancestral houses; an Anglo-Irish Gothic doom, misanthropy, and exploration of fantasy lands was rooted for him in Swift’s Gulliver’s Travels; next the mythic imagination of Yeats and AE (George Russell) urged on him the possibility of a lyrical search for esoteric spiritual imagery; his study and devotion to the British Romantic and Victorian poetic imagination provided him with a critique of materialism, mechanization, and modern urban homogeneity; and, Nietzsche’s fables, phrasing, and bristling energy critiquing orthodox images of religion offered inspiration particularly from Thus Spake Zarathustra. His fables draw from these sources to remake the universe as a holy aesthetic mythopoeic vision rather than a religious orthodoxy in which a numinous Gothic doom is paradoxically working simultaneously with a Romantic evocation of Nature’s beauty.

Yet Dunsany is often like some Anglo-Irish Oberon draped in a toxic cloak of invisibility, for such touchstones of literary criticism as the epochal but controversial 1991 three volume Field Day Anthology of Irish Literature and Declan Kiberd’s 1995 Inventing Ireland: The Literature of the Modern Nation completely ignore him and Dunsany merits hardly a mention in The Cambridge History of Irish Literature (Volume II). He receives only a few scattered references – mostly condescending and dismissive (“WBY made some new acquaintances – including Horace Plunkett’s cousin Lord Dunsany, who wrote fantasy-tales from his appropriately fairy-tale castle outside Dublin”) – in Roy Foster’s magisterial 1998 first volume W.B. Yeats: A Life – The Apprentice Mage. And those references are also unfortunately inaccurate (Horace Plunkett was his uncle.)

Indeed the example of Foster is instructive as a scholarly, comprehensive and authoritative contemporary biography on the scale of Foster’s work is much needed as English author Mark Amory’s infamously lackluster and error-pocked 1972 biography, Lord Dunsany, treats Dunsany’s Irish contexts with superficial and scant detail lacking any insight into cultural nationalism and the convulsions in identity and loyalty for Dunsany that followed the Easter Rising of 1916. Amory’s biography is notorious for not mentioning the actual day or month of Dunsany’s birth and jumbling the chronology of his publications. The need for Irish scholarship to place Dunsany in his literary and socio-political contexts is only made more acute by the unintentional errors of serious-minded American fantasy fiction scholars. For example, the revelatory Penguin Classics anthology In the Land of Time and Other Fantasy Tales (2004) which revealed the breadth of Dunsany’s achievement over five decades was edited, introduced and annotated by the eminent Lovecraft biographer and Dunsany bibliographer and scholar, S.T. Joshi who offered the following eyebrow-raising summary of the Easter Rising: “Dunsany was seriously injured during the Dublin riots of 1916.” Surely, an Irish scholar would have been more aware of the significance of the Proclamation of an Irish Republic!

Yet the family had extraordinary roots in Ireland as his biographer underlines: “There had been Plunketts living at Dunsany Castle, 20 miles north-west of Dublin, since 1190.” The Castle can make the claim to being one of the longest continuously inhabited residences in Ireland. But Dunsany’s allegiances were primarily with England, the Empire, and the union. “Their values and friends came largely from the English upper classes. . .[his biographer, Amory adds] In a rebellion their instinctive loyalty would be to the government of Westminster.” Following the relatively typical inevitabilities of hybrid and hyphenated Anglo-Irish identity, he would crisscross repeatedly between Ireland and England and be permanently caught in between both. Ireland was the emotional hub as the site of the ancient family seat and parental proximity, but England and Englishness loomed large in his imaginative formation as the place of education (where he would be uprooted into boarding school) and empire (where he would be trained to be an army officer) and power (where he would unsuccessfully try for a political career).

Through his childhood and adolescence his mother had disdained newspapers encouraging him to read the Bible instead and he was particularly steeped in the Old Testament with the Book of Genesis a clear source for his direct and vivid archetypal prose. He absorbed a kind of slow-stepping, dignified and stately rhythm in his prose music from his constant attention to the Bible. In adolescence, he worked his way through the collected tales of Edgar Allan Poe deepening his style with Gothic dread. He was educated at Eton beginning in 1891 where he absorbed both a conventional commitment to British imperialism and a classical curriculum becoming particularly enthusiastic about Homer’s Odyssey. Its celebration of the numinous mystery and magic of the intertwining rivers of myth and fable, of strange exotic lands, and an all- encompassing realm of the gods he acknowledged as a primary fountainhead to his inspiration. Horace (sections of whose Odes he learned by heart) was supplemented by reading of the British Romantic poets Blake (with his own strange and august pantheon of beings), Keats, Shelley, Byron, Coleridge, and Wordsworth. Their lyricism would add an inner luminosity and myriad colors to his Biblically-inflected prose poetry. Finally, the great Victorian Tennyson’s Arthurian Idylls of the King with its enchantments, magic swords, and inevitable doom provided a model and influence.

The military training of Sandhurst college followed Eton and after his father’s death in 1899, he enrolled as an officer in the Coldstream Guards and was shipped to Gibraltar where his imagination saturated in literary sources was fired by this exotic vista: “firmly holding that Tangier is of the East, he came to feel that this first glimpse was the basic inspiration of his finest work.” Shortly afterwards he was posted to South Africa during the Boer War where he met Kipling. Weary of military routine, he departed the British army in 1901. Back in Ireland, fox hunting and shooting every type of creature and bird occupied him from 1902-1903 after he accepted the Mastership of the Tara hunt and careened on horseback enthusiastically across the Meath countryside. Felling pheasant, geese, snipe, teal, woodcock and plover, supplemented with rabbits (with over a thousand prodigiously bagged in a three month stint), saw him enthusiastically shooting his evening meal from October to March. Famously, he is reputed to have shot the Castle’s doorbell from afar to avoid waiting for the butler while striding home from one rabbit hunt. The topography of the Irish countryside was as important to his lyrical imagination as any of his African vistas. Lengthy descriptions of the hunt and shooting and the bogs with “the beauty of one evening hallowing the moss and the heather” of the surrounding Meath countryside feature in his autobiographical 1933 Irish novel, The Curse of the Wise Woman.

Undoubtedly privileged within an Anglo-Irish upper class social round, he filled out his time back in Ireland with cricket, chess, crossword puzzles, and charades on the 1,400 acre estate with its capacious and centuries-old library as he successfully courted and married Lady Beatrice Villiers in 1904 and invited her to supervise their fifteen servants. While he made an unsuccessful attempt as a West Wiltshire Tory candidate in 1904, his love of writing tales was encouraged by his new English bride. His uncle Horace Plunkett ran the Irish estate, but also was deeply connected to the Irish Literary Revival having met both Yeats, who gave a label to the movement with the publication of The Celtic Twilight in 1893, and Lady Gregory in 1896 and who also worked closely with George Russell (AE) from 1897 in the Irish Cooperative movement. The catalyst for writing his first book of tales may well have been Dunsany’s acquaintance with AE who had visions of gods (albeit Celtic), seeing in London the play The Darling of the Gods, a treatment of Japanese mythology by the American writers David Belasco and John Luther Long, and his deep immersion in the King James Bible, Greek mythology, and the philosophical fables of Friedrich Nietszche.

Dunsany as an Anglo-Irish author was a brilliantly innovative pioneer from his very first book. He was the first original creator of a complete modern fantasy cosmogony: the Pegāna Mythos. Dunsany created his own mythology in his self-financed work, The Gods of Pegāna (1905). It was a sensation and established his reputation. He never had to self-finance a book again in his fifty year career. The basic premise of the book is the complete unknowability of the purpose of the universe as the ultimate god, MĀNĀ-YOOD-SUSHĀĪ, is put into a state of cosmic dreaming by Skarl the drummer after creating the smaller gods. Once Skarl ceases his drumming, the ultimate god will awake and all will cease. This is the terror of the smaller gods for they and all of the universe are but dreams in the mind of the ultimate god. “But, when at the last the arm of Skarl shall cease to beat his drum, silence shall startle Pegāna like thunder in a cave, and MĀNĀ-YOOD-SUSHĀĪ shall cease to rest. Then shall Skarl put his drum upon his back and walk forth into the void beyond the worlds, because it is THE END, and the work of Skarl is over.” He followed this with his second Pegana book, Time and the Gods (1906) in which Time becomes more fully the doom and scourge of the gods themselves. But doom and the void, key motifs combining dread and the Anglo-Irish Gothic imagination with a Nietzschean proto-Beckettian sense of the cosmic Absurd, are already indelibly established.

His formal involvement with the Irish Revival began with the publication of his tale “Time and the Gods” in the first issue of Shanachie in 1906 and it was followed by another tale “The Fall of Babbulkund” in AE’s Irish Homestead in Christmas, 1907. He published The Sword of Welleran and Other Stories (1908) which melded visually exquisite exotic cities in strange fabled lands with narrative trajectories of Gothic doom. He began visiting the luminaries of the Irish Revival, attending gatherings of poets at AE’s home (where he first met Francis Ledwidge in 1909) and began hosting William Butler Yeats and Lady Gregory and AE at Dunsany Castle from 1909. But unlike cultural nationalists like W.B. Yeats, Dunsany did not support the break with England. This opposition to Irish nationalism would see him marginalized and written out of the narrative of the Irish Literary Renaissance.

Initially, there was an enthusiastic rapport between the Dunsanys and the moving personalities behind the Irish Literary Revival as “At first, he, and Beatrice when she returned, adored Yeats.” Both agreed that Yeats was a genius, and Dunsany wrote to his wife: “AE is a marvelous genius.” By March 1909, he was writing with a sense of awe: “I have been among great men.” It was to Yeats that Dunsany owed his subsequent blossoming as a dramatist. Yeats wrote to his father in 1909, “Dunsany is a man of genius, I think. . . I want to get him into “the movement.” During a conversation in 1909 in the Kildare Arts Club, Yeats invited him to write for the recently formed (1904) Abbey Theatre. His first Abbey play written at breakneck speed in one afternoon was presented in April 1909. The one act play, The Glittering Gate, continued the Nietzschean skepticism towards religion already evident in his two Pegana books as it depicted two burglars trying to break into the solid gold gate of Heaven and discovering nothing within only: “Stars. Great Blooming Stars.” An unexplained cosmic laughter erupts around them from an off-stage source. Its comic male duo who are endlessly popping bottles of beer and the premise of waiting for a cosmic revelation that is disappointed make it seem a proto-Godot that may have influenced Beckett. It certainly could be classified as an early Irish instance of the Theatre of the Absurd long before that phrase was coinedand was as brilliantly original in another genre as his first fantasy tale collection in 1905.

It was followed by King Argimentenes and the Unknown Warrior in 1911. Both plays were successful and in the void left by the death of Synge in 1909, Yeats seemed to have found a new voice for the Revival. However, Dunsany and his wife believed the latter play was plagiarized by Lady Gregory in her The Deliverer (which was presented at the Abbey two weeks before Dunsany’s play and their suspicions deepened when neither Yeats nor Gregory in an unusual break from tradition in their view attended his opening night). They termed Gregory the ‘Bad Old Woman in Black’ (after the title of one of his stories) and his enthusiasm for the Revival chilled.

His biographer lists several “small reasons” why Dunsany couldn’t simply join the Irish Renaissance group: the Castle was too far from Dublin, his politics were too Unionist, his culture was too English (“The books that influenced him had been part of a traditional English education”), and he had no real love for Irish literature, mythology or the Gaelic language. Significantly, Padraic Colum stayed at Dunsany Castle in 1911 and the dinner descended into a “heated argument. . . it is difficult [his wife observed] for him and an advanced nationalist to agree.” More importantly, he was too independent and “had not the character to fit easily into any group particularly in a subordinate position.” There would only be one commanding officer of the Irish Literary Revival and that was Yeats. Oliver St. John Gogarty who was a devoted friend of the Dunsanys and a frequent guest at their castle wrote an astute assessment of how envious Yeats was of Dunsany’s status and pedigree:

It would be a mistake to think that the rivalry between Dunsany and Yeats was a literary one. Far from it. Yeats had no rival to fear among contemporary poets. It was not so much rivalry on Yeats’ part (shocking to say it before it can be explained) as it was envy. Yeats, though his descent was from parsons, dearly loved a lord. He was at heart an aristocrat, and it must always have been a disappointment to him that he was not born one. Not by taking thought could he trace his descent from the year 1181. . . This then was at the bottom the cause of the failure of friendship between Dunsany and Yeats.

While he would remain friends for life with Oliver St. John Gogarty, James Stephens, and Padraic Colum, the relationship with Yeats and Gregory soured and deteriorated by 1912 when in an ironic twist Yeats presented The Selected Writings of Lord Dunsany from his sisters’ Cuala Press with an “Introduction” that sounded a note of profound appreciation and affectionate regret:

Had I read The Fall of Babbulkund or Idle Days on the Yann when a boy I had perhaps been changed for better or worse and looked to that first reading as the creation of my world; for when we are young the less circumstantial the further from common life a book is, the more does it touch our hearts and make us dream. We are idle, unhappy and exorbitant, and like the young Blake admit no city beautiful that is not paved with gold and silver.

Dunsany transcended his irritation at Yeats and Gregory with prolific industry. The Book of Wonder (1912), Five Plays (1914), Fifty-One Tales (1915), and The Last Book of Wonder (1916) appeared and consolidated his reputation despite World War One. The intervention of physical force Irish nationalism created a further distance between him and the Literary Revival with the Proclamation of the Irish Republic on Easter Monday, April 24, initiating the Easter Rising in Dublin’s G.P.O. Dunsany raised to the rank of Captain in the Royal Inniskilling Fusiliers hurtled into the city with his chauffeur and was caught in the crossfire of a rebel ambush on his way to Amiens railway station and was hit near his eye. The nationalists allowed him to be taken across rebel lines to receive medical attention at the Jervis Street Hospital where he spent the week ministered to by nuns who pried bullets out of window frames with disgusted comments about the “nasty little things.”

But if Dunsany’s standing in the Irish Literary Revival was becoming more problematic, a larger recognition in America was demonstrated by the first of two Modern Library editions beginning with A Dreamer’s Tales and Other Stories (1917), which was a combination of the earlier collections The Sword of Welleran and A Dreamer’s Tales. Padraic Colum’s “Introduction” depicted Dunsany as a “fabulist” who was interested in asking what the moon was made of rather than being a conventional fiction writer – instead he traded in wonder and myth. It is clear from this “Introduction” that Dunsany was comfortable with being an Irish fabulist rather than being a Yeatsian protégé. Another Modern Library edition, The Book of Wonder (1918) combined Time and the Gods with the earlier The Book of Wonder. The increased prestige of these editions was cemented by Dunsany’s successful lecture tour of America in 1919, made legendary because Lovecraft attended the Boston lecture in October. He would prove to be the most influential devotee and imitator of Dunsany’s cosmic tales and it is Lovecraftians that fueled the varied Dunsany revivals of the 1970s and the 1990s.

Significantly, in assessing the vexed question of Dunsany’s role in Irish fantasy fiction, the wheel of Irish history is against him, particularly as Irish nationalism heavily inflected with triumphalist Catholicism rewrote Ireland’s cultural narrative following the revolutionary period from 1916-1923. His uncle Horace’s home in Foxrock, Kilteragh, was burned to the ground during the Irish Civil War (1922-23) precipitating a dejected move to England where he passed away in 1932. Dunsany Castle was briefly threatened but the family’s status amongst the locals as benevolent landlords meant it wasn’t torched and word-of-mouth spread insisting it be left alone. A quartet of gunmen come to assassinate the owner of the estate in the opening pages of his autobiographical 1933 Irish novel, The Curse of the Wise Woman showing Dunsany’s awareness of his precarious Anglo-Irish condition in the new Irish Free state.

Darrell Schweitzer’s critical study Pathways to Elfland: The Writings of Lord Dunsany (1989), the first complete survey of all of Dunsany’s oeuvre in all genres, argues that the rhythms of his career involve “working extensively in one literary mode (short story, play, novel, etc.) to exhaustion.” The 1920s saw Dunsany move from tales and plays to writing novels beginning with the slight The Chronicles of Rodriguez (1922) peaking with the classic work The King of Elfland’s Daughter (1924) which featured the Anglo-Irish theme of power moving from one ancient regime to a new unsettling order that would have been close to Dunsany’s experience as he had been nearly shot dead in 1916 and his castle had nearly been burned down in the 1922-1923 Civil War. It depicts the land of Erl’s men approaching their lord “the stately white-haired man in his long red room” but they do so to replace him even though as their spokesman tells him: “For seven hundred years the chiefs of your race have ruled us well. . . And yet the generations stream away, and there is no new thing.” The lord asked what they want and they reply: “We would be ruled by a magic lord.” He followed this with The Charwoman’s Shadow (1926) and The Blessing of Pan (1927).

In the 1930s, the call of Ireland proved irresistible. His old antagonists, Yeats and Lady Gregory set up the Irish Academy of Letters in 1932 which initially created a two tier membership structure. “Academicians” did creative work with Irish topics while “Associates” didn’t, but were instead of Irish descent or birth. Dunsany was deeply irritated to be assigned only as an Associate. In response he wrote his most autobiographical Irish novel, The Curse of the Wise Woman (1933) which Joshi considers as “probably his finest novel.” The novel could be basically seen as Dunsany’s cri de coeur declaring passionately that he had become (and perhaps always was) as Irish-as-the-Irish-themselves in response to living in the Irish Free state where the authentic Irish-ness of the Anglo-Irish was questioned or denied. They were frequently disparaged as West Britons because they lacked nationalist, Irish language, and Catholic moorings.

The premise of the novel involves a Dunsany persona, Charles James Pedimore, now living in an unnamed central European country who remembers the Ireland he grew up in fifty years ago. It was “a beautiful and happy country” and “not a sad and oppressed country, as some say.” Like Dunsany in his youth, he is an Irish country gentleman’s son who lives in an extensive estate. The catalyst for the plot is four Catholic gunmen invade their hall but his father mysteriously vanishes and so they threaten to burn the house but are abashed when a piece of the True Cross, a family heirloom, is produced clearly establishing that this is a Catholic land holding family. His father has spoken out in an unspecified political issue and has been condemned. The son left alone is initiated into hunting on the bog which becomes an all-encompassing symbol revealing the essence of Ireland: “but it [the bog] lulls him and soothes him all his days, it gives him myriads of pieces of sky to look at about his feet, and mosses more brilliant than anything short of jewelry.”

The Dunsany persona’s reverential memories of shooting geese and going on fox hunts – essentials of Dunsany’s Anglo-Irish upbringing in a British Ireland – become for this Catholic version of Dunsany a way of claiming an identity aligned with the essence of Ireland itself. First, the character is halted because “the cry of the curlew seems to me to be the voice of Ireland.” His guide, Marlin, in teaching him how to shoot snipe on the bog warns him that his mother is a Wise Woman (a witch) and that he has sinned because he has dreamed of Tir-Nan-Og, the country of the young from Irish mythology, where he wishes to go instead of the Catholic Heaven. “Its morning forever over all the land of youth. . . I had preferred Tir-Nan-Og to Heaven,. . . For him there would never be anything but that most heathen land.” The Wise Woman who seems like an archetype of Mother Ireland and who tells him she sees an Ireland with a fabulous future of glorious cities trading proudly with all the world’s nations. Here the fabulous visions of his earlier tales are transposed to an Irish setting, one that insists on the bog with its metamorphoses of weather and its birds (snipe and geese) that are hunted or that journey, like the kingfisher, between Ireland and Tir-Nan-Nog. The persona (in his dreaminess echoing Dunsany’s view of his younger self) finds in his guide’s belief in Tir-Nan-Nog a way to again transcend the socio-political map of a mundane Ireland: “It is strange indeed that talking of Tir-Nan-Og seemed to strengthen its frontiers. . . He [Marlin] was so clearly a citizen of Tir-Nan-Og, and yet he lived here on the solid land that is mapped; and the thought of him linked the two lands, as that sunlit stretch of water out by the bog’s horizon seemed to link them whenever I saw it.” He hears that the son has been guided by a rainbow and has left for the land of the “everlasting morning.” The son asks the Wise Woman to curse the industrial company that has come to cultivate and destroy the bog. Through doing so, they will save the “heart of Ireland.”

The bog itself was threatened. . . all were to be spoiled, hidden, sold and disenchanted by that terrible force named Progress. . . The very heart of Ireland appeared to be threatened, for the bog seemed that to me then. . . I foresaw the bog vulgarized by noise and machinery.

The novel ends with the witch’s curse creating a doom in the form of an apocalyptic storm that swells the bog itself with sufficient force to sweep away the manifestations of modern progress, to destroy the sheds and machines of the company, and allow the bog as the “heart of Ireland” to be saved. The Wise Woman is a wild and numinous Gothic representation of an archetype of Mother Ireland that is beyond the conventions of Irish Free State nationalist ideology. This is clearly seen in the crescendo of the novel when she immerses herself in her ritualistic curse:

Lovingly she spoke to the bog, bending down to it over the mosses, crooning to it and softly beseeching it; but what she said to it I do not know, for she was talking now that language that seemed older than Irish, which I had once heard her use before, and which certainly was no language that men speak now.

The major concerns that sounded from the beginning of his career: a tragic sense of doom and Gothic enchantment (the witch in this novel is a classic Gothic type), a Blakean critique of the satanic mills of materialistic industrialization, a determination to evoke the Homeric rivers of fable and myth are combined with a post-Irish Free State 1930s sense that his imagination had found a redeeming narrative construct of Irishness in the character’s possession of the True Cross, being moved by meditating on the beauty of the bog, hearing the curlew’s cry, seeing the vision of Tir-Nan-nog, and saving the bog from destruction. Any critique of Anglo-Irish inauthenticity is transcended.

Support CJAC’s ‘Mural in the Midway’

Carillon RoseMeadows

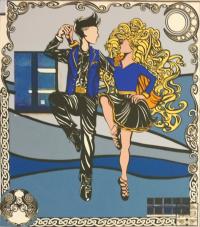

With the goal of making the outside of our building reflect the activities inside, artists Marty Ochs and Carrie Finnegan have been hard at work producing the large-scale 70’x20′ mural of the thriving Twin Cities Celtic arts scene. The mural on our south wall represents the four pillars of The Celtic Junction Arts Center: music, dance, education, and community. This artwork is a ten year anniversary gift to ourselves, our community, and the Midway neighborhood – and we’ll all be enjoying it for years to come! We have until September 1 to meet our fundraising goal of $4000 and earn a matching grant of $500 from Midway Murals, an organisation which generously granted us $500 at the start of our project. You’ll stretch your dollars by contributing now and the money will go directly to the artists.

Marty is a freelance artist and co-proprietor of Casey’s Cache, where she, along with her husband, create and sell unique Celtic inspired leather art and items at fairs and festivals in the Upper Midwest. Over her career, Marty has won several awards for her sculpture and two-dimensional art. From fine art to illustration, this versatile artist takes great joy in projects that serve and support the community.

Carrie Finnigan uses a playful approach to painting, printmaking, and drawing of abstracted representations of human figures and nature. Growing up in close proximity to forests and water, she developed an affinity with the outdoors and was fascinated by the human – natural environment conflict. This youthful interest was formally developed in a B.A. in Fine Art. She delved into artistic practice, honing her preference for using color and line to express emotion.

Marty and Carrie are fusing traditional Celtic artwork with a contemporary interpretation of the Art Nouveau style which incorporates the curves and strong lines distinctive in Celtic knots without the strict and time-consuming rule-based approach of knotwork. Art Nouveau combines the sense of impressive complexity in Celtic art design with a fluid, organic, and natural feel. The arts practiced inside the Celtic Junction are part of a living tradition and not rigidly bound to historical precedent; reflecting this, the artists have playfully explored their take on Irish art during the design process.

Visit our project on GiveMN and support our Mural in the Midway.

Tale One: The Legend of Billy in the Bowl

By Patrick O’Donnell

[Editor’s note: The Map-Maker’s Tales is a new collection of fantasy tales for young adults – of all ages! It involves a young female map-maker, suffering from an unnamed psychological trauma, returning from Minnesota to undergo an apprenticeship under the tutelage of a mysterious old professor who is deeply learned in the esoteric lore of Old Dublin.]

The great professor shifted his ample bulk in his huge-winged armchair toppling a pile of leathery capacious volumes on to the stone floor of his study. The map-maker hastened to collect and return them exactly to their former totteringly precarious location. The great professor, she well knew, could not abide tidiness. Chaos was the sauce of learning, he always insisted with a belligerent and dismissive wave of his large hands. The map-maker silently did not agree with the aphorism. She would reverse it completely, but she never argued with the great professor. At least not until – she thought, as a smile ghosted across her thin high-boned face – he was done telling his strange tales.

The great professor’s severe and coal-illuminated face did not register any acknowledgement of this event. He appeared to be motionless but the strangely intense silver light in his eyes gave notice that he was wandering deep inside the subtle and serpentine labyrinth of his memories. Shadow-pocked, ruminative, flesh-heavy, and hedge-bearded, his countenance was like a map all on its own, thought the map-maker. Could one map someone’s mind? Was the mind a city with a past like these maps of old Dublin? Or more like an architectural drawing of some fine and cunning old building?

The map-maker unfolded her vellum map of Dublin in the eighteenth century and waited as a fisherman might pause above a lake watchful for the sharp razor-toothed jaws of an enormous and wily grandfather pike – watchful but certain that the pike would take the bait just as the map- maker knew that the sight and faint aroma of the vellum manuscript would provoke the great professor to strike. Silence hung in the room like a tapestry heavy with gilt and ambrosial tints.

The great professor stirred and lifted his carved swan-bellied pipe, inhaled vigorously, sighed, and exhaled a tornado-like funnel cloud of noxious and debilitating odor. He began his next tale while the map-maker scribbled and scrawled notes with a determined industry.

My father, he began, remembered this tale which was told to him by his own father who had met the protagonist personally and indeed had been threatened by him with a knife. The character of which I speak was a most belligerent and disagreeable fellow called Billy in the Bowl, a thief, a beggar, and one of the most sorry sights that you would meet ambling through the cobbled streets and by the old meat and fish markets adjacent to Fishamble Street below Christchurch Cathedral.

He was born with a singular deformity. He had no legs. So his parents, not knowing what else to do, placed him in a large wooden bowl. He grew up cantankerous and ill-willed but huge of shoulder and enormously strong of arm as he propelled himself through Dublin’s streets by this method. It was a signature sound on the rounded cobble stones and under the shadowed arches of the Cathedral to see and hear his clunking clonking progress – a fierce figure in a worsted overcoat and sham squire square hat with an enormous hedge of thorny and unruly beard and ferocious glowering eyes like dagger points squinting and glaring at the populace as he heaved himself along – a torso crowned with a malevolent head contained in a large battered old wooden bowl.

The poor people of the city – and indeed he was one of their own – gave him the name “Billy in the Bowl.” Indeed it summed him up with a fatal accuracy and precision that he loathed. He wanted to be a William or a Liam – Billy seemed both egregiously affectionate and childish and the term “bowl,” well, that was just galling as it reminded him incessantly of his beleaguered and truncated physical appearance and his ignominious status in life. Never mind his mode of transportation and housing!

When it rained, he would hasten under the arches but he was often too slow and had to suffer the indignity of having rain sloshing about in his bowl. It did not improve his temper or mood. Indeed it would aggravate his usual condition of ill temper into a black fury and great retching streams of curses and invective and burning maledictions would pour out of him like a cauldron tipping over boiling oil from the ramparts of a besieged citadel. All the citizens of the city would avoid him and his rain-clogged bowl at such moments. So foul was his temper that even the stolid gray stones of the Cathedral’s arches would seem to shrink back in fear and disgust from his presence. His face, as the old expression had it, looked like a plate full of mortal sins.

He made his living as a beggar. Only the unfamiliar, the unlucky, or the naïve were persuaded by his surly appearance in his huge wooden bowl to offer him a pittance of pennies and half pennies. A dark thought grew in his mind. He would become a thief. He would steal from the ladies promenading on the lawn at Dublin Castle.

First, he heaved his bulky wooden bowl down the cobbled lanes to the cutlers who sold and polished knives for the cooks and butchers who worked for the mansions of the English-born garrison. He flung a pouch full of pennies on the counter.

– Give me your longest and sharpest butcher’s knife.

– Why?

– I want to cut my toenails, he snapped. Why do you think?

The apprehensive cutler slid over one of his most gruesome butcher’s knives to the ill-tempered beggar, who that afternoon clunked his way – hidden by the tall wheels of a supply wagon – into the Castle Yard.

Dublin Castle and its annual ball was an exclusive and ornate affair. The ladies – glittering in lace and muslin with faces creamy and rose-tinted – were English-born gentlewomen of the Dublin garrison largely ignorant and protected from any accurate knowledge of Dublin’s beggar class. They thought the odd figure of the hefty gentleman in his battered hat and even more battered bowl was a part of the masque entertainment for that night – a clown perhaps, a picturesque and amusing figure from the lower Irish native classes. The word “native” hung on their tongues like a particularly vehement venom, harmless to them but lethal to the object at which it pointed.

Two of them, with a rustle and a giggle and a nudge of mutual encouragement, moved over to inspect him and engage in raillery and witty banter with, as they whispered, one of the “charming natives.” He glared up at them with eyes sharp as fish hooks. They halted before him in disquiet as the sheer malevolence of his spiteful countenance caused them to shudder. With a growl and a curse, he produced his butcher knife and demanded their money. The women jumped in shock as though thrown in the air by an invisible force. They hastily dropped gold sovereigns into his gritty palm and retreated. He stumped off triumphantly in his ungainly old bowl.

Now the ladies were faced with a dilemma. They had been shocked by the knife, but more completely shocked by the reality of the legless old beggar slumped in his cracked, stained, and battered wooden bowl with a face as wracked and warped and repellent as a mountain-edge thorn bush. Poor Billy in the Bowl believed that he was a heroic figure, a hero defying authority and the British garrison, but, as the rain water splashed out of his bowl while he splayed out his massive arms to lift and thump it across the lawn before halting to hide beneath a sculptured hedgerow in the Castle grounds, the ladies had conferred amongst themselves and had resolved to permit Billy in the Bowl to remain. They wouldn’t let the soldiers arrest him. Instead they moved among the other ladies telling their tale and nodding over at the poorly hidden Billy.

In groups of two and three, they allowed themselves to wander past him and to be surprised by the ferocious thief and beggar, allowed themselves to be menaced by the shining threat of the butcher’s knife, and allowed the beggar to clomp off to hide once again – in plain sight to the wary – beneath the sculptured hedge of the lawn. All afternoon and evening, he triumphantly clomped out to steal and they equally shed their sovereigns like golden shimmering petals into his increasingly burdened bowl.

At night, with the guards and soldiers carefully instructed not to notice him, Billy in the Bowl clunked off out of the Castle gardens to lurk and sleep under the Cathedral arches with a harvest of golden glittering sovereigns brimming in his beggarly ould bowl.

– The greatest robber in the history of Dublin, Billy murmured to himself on the lip of sleep. The greatest! A legend!

But, said the great professor, emerging out of the syncopated reverie that his own voice had induced, that was only the start of the legend of Billy in the Bowl!

He reached down into the wooden chest that sat with its lid yawning open and grasping an old butcher’s blade, sent it whirring in a blur across the room towards the bent head of the map-maker. She plucked it out of the air by its oaken hilt and stabbed it into the pocked desk where she was working.

Has it ever been used to kill, she asked glancing expressionlessly at the fierce old professor.

Never, he growled.

There is always a first time, she smiled, gracing him with a wink that caused him to sink watchfully back into his high winged armchair. Glancing at the knife, she inked its gleaming image within the outline of Dublin Castle’s ample grounds on her vellum map.