Issue 2, Samhain 2017

Irish-American Nationalists and American involvement in the First World War · Michael Dean: Indefatigable Irish-Minnesotan Singer and Songcatcher · The Home Place: Brian Friel’s Ireland · The Importance of Lord Dunsany

Introduction to the Celtic Junction Arts Review, Samhain 2017

Welcome to the second installment of the Celtic Junction’s online quarterly cultural arts magazine. Aligning ourselves with the legendary ancient divisions of the Celtic year, this edition appears in accord with Samhain, the ancient Féile na Marbh (festival of the dead) when traditionally the barrier between this world and that of the dead became thin and porous and spirits of the departed could traverse the Earth. Similarly, in this edition several ghosts walk and speak to us.

Brian Miller, the Eoin McKiernan Library Director, resurrects the Irish songcatching phantom of Michael Dean (1858-1931) who labored for decades in Minnesota’s lumber trade and also owned and operated saloons. Dean’s songster, “The Flying Cloud” (1922) containing 166 texts – including ballads, music hall songs, and poems for recitation –solidifies the scholarly argument that the bunk houses where the workers wintered amidst the white pine forests of northern and central Minnesota were dominated for decades by Irish song and singing styles. Dean, a jovial, self-deprecating, and restless figure was recognized as an authority on Irish song by academic song collectors such as Franz Rickaby in his “Ballads and Songs of the Shanty Boy” (1923). Dean also corresponded with such eminent American literary figures as Carl Sandburg.

Anthony Roche, Professor Emeritus in the School of English, Drama, and Film at University College Dublin, resurrects the ghostly figures of the great Irish playwright, Brian Friel (1929-2015) and his inspirational mentor, the great Anglo-Irish director, Sir Tyrone Guthrie (1900-1971). Guthrie, in his early sixties, acted as a father in the theatre for Friel, in his early thirties, when he invited him in 1963 to attend the rehearsals of the inaugural season of the Guthrie Theater in Minneapolis. Professor Roche’s article offers a “world exclusive” in literary history as the Literary Estate of Brian Friel has given him permission to access for the first time the diaries that Friel composed at that period. Friel, fundamentally pigmented by his Minneapolis sojourn in 1963, went on to transform himself into undoubtedly the most eminent and important Irish playwright from 1964 until his passing in 2015.

Michael Doorley, Associate Lecturer in history and international relations with the Open University, offers an account of Irish-American nationalism in 1917. He examines the response of Irish-American nationalists to the First World War and their efforts to win recognition for Irish independence after the War. Professor Doorley holds a special place of honor in relation to the Eoin McKiernan Library as his talk on this topic was the very first academic talk in that new space in April, 2017. Fittingly, it was given as part of the second annual Saint Paul Irish Arts Week on the one hundred and first anniversary of the reading of the Proclamation of the Irish Republic on April 24, 1916. Indeed before his talk, John Concannon, the Galway-born Vietnam veteran and actor with Celtic Collaborative gave an impromptu performance of the Proclamation!

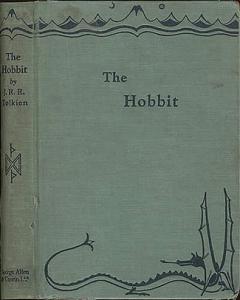

My article allows the spirit of the great pioneering Anglo-Irish author of twentieth century cosmic fantasy fiction, Lord Dunsany (1878-1957) to walk abroad once more. Celebrated for his inspirational influence on authors as varied as H. P. Lovecraft and J.R.R. Tolkien and Neil Gaiman, and writing in a variety of genres over five decades, Dunsany, who visited Minnesota on a lecture tour in 1919, is arguably the founding “grandfather” of speculative imaginative fiction. What is beyond dispute is that he is easily one of the most extraordinary – and little known – geniuses in the Irish Literary Renaissance. This article will also form the abbreviated basis for the Colloquium on Dunsany on Saturday, November 18, in the McKiernan Library.

Irish-American Nationalists and American involvement in the First World War

Michael Doorley

The year 2017 represents the centenary year of the United States’ entry into the First World War on the side of Britain and France and against Germany and Austro-Hungary. It took some time for the US to fully mobilize it’s considerable economic and demographic resources but by early 1918, American troops had already begun to turn the tide of battle and they played a decisive role in achieving the final Allied victory in November 1918. American combat deaths in the First World War numbered 53,000 though if one includes deaths from disease, the overall figure rises to 116,000. This made it the third costliest military campaign in American history after the Second World War and Civil War but today American participation in this war has been largely forgotten.

In this article, I would like to explore the attitude of Irish-American nationalists to the First World War in Europe and also examine how Irish-America sought to raise funds and win United States diplomatic recognition of an independent Ireland after the war.

Prior to the outbreak of the war in Europe in 1914, most Irish-Americans favored Irish leader John Redmond’s parliamentary efforts to secure Home Rule. This measure would have given Ireland a limited form of independence but would have denied Ireland its own army and the ability to conduct its own foreign policy. However, a minority of Irish-Americans backed John Devoy’s New York based Clan na Gael who wanted to establish an independent Irish Republic through revolutionary means. The Clan worked closely with its sister organization in Ireland, the Irish Republican Brotherhood (IRB). Even though the Clan was relatively small, probably about 10,000 members, the IRB was even smaller and depended on Irish-America for financial and moral support.

Britain’s decision to enter the war against Germany and John Redmond’s support for the British war effort led to a sea change in Irish-American nationalist opinion. Even the Irish World newspaper, which had been along-time supporter of the Irish Parliamentary Party, declared that for Redmond to ‘fritter away any part of her [Ireland’s] military resources would be treason of the blackest kind’. The Clan na Gael now seized the opportunity to create a more broad-based organization which would appeal to mainstream Irish-American opinion. New York State Supreme Court Justice Daniel Cohalan, a trusted confident of Devoy, helped found the Friends of Irish Freedom (FOIF) organisation at the New York Irish Race Convention in March 1916.

The recent publication Ireland’s Allies: American and the 1916 Easter Rising (2016) edited by Miriam Nyhan Grey has documented the Irish-American contribution to the 1916 Rising. As Joe Lee in the introduction to the book declares: ‘No America, No New York, No Easter Rising. Simple as that’. However, the Clan and the FOIF had other more American-centric goals. With some justification, Cohalan and Devoy feared that Britain was trying to enlist American help in its war against Germany by means of a propaganda campaign in the US. The FOIF mounted a counterpropaganda campaign calling for American neutrality and the Clan’s newspaper, the Gaelic American even took a strong pro-German line. Following the 1916 Easter Rising, the FOIF held public demonstrations condemning the executions of rebel prisoners but these demonstrations also opposed the entry of the United States into the European war. On the 4th February 1917, at a New York public meeting of the FOIF, Justice Cohalan declared that if the United States fought on the side of the Allies, it ‘would be fighting for the combined subjection of Ireland, India and Egypt to English rule’, (New York Times, 6 April 1917).

Cohalan’s campaign to keep the United States out of the war in Europe failed in the face of deteriorating relations between the United States and Germany, particularly in relation to the resumption of unrestricted German submarine warfare which targeted American ships supplying goods to the Allies. On the 6th April 1917, the United States declared war on Germany. This presented Irish-American nationalists with a dilemma. As part of their efforts to gain acceptance in the United States, they had traditionally demonstrated their loyalty to the nation through willing service in the American military. Now the United States was at war with Germany and allied with Britain, the traditional enemy of radical Irish-American nationalists. How should they react to this new situation?

Wary of being accused of disloyalty in what became a feverish war-time atmosphere, the Clan abandoned all support for Germany and called on its members to remain loyal and ‘yield to none in devotion to the flag’. In an interview with the Catholic newspaper, The Brooklyn Tablet, Cohalan declared that Irish-Americans would always be ‘present in defense of the flag and support of American institutions’. (21 April 1917).

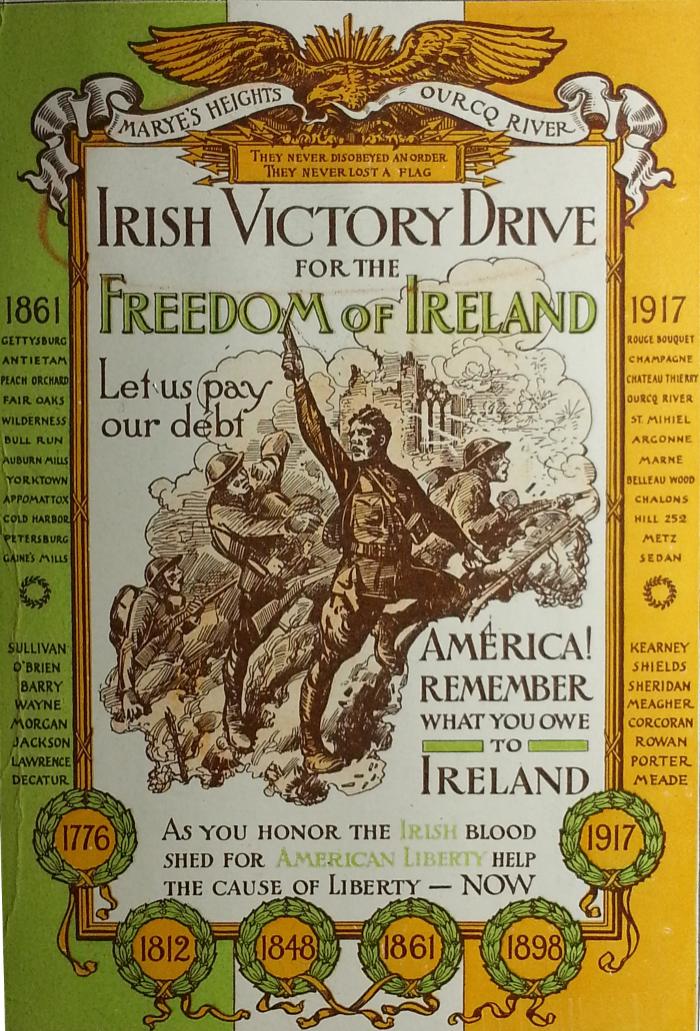

Cohalan pledged Irish-American loyalty to the war effort but also attempted to link the Irish cause to President Woodrow Wilson’s vision of a war being fought for the rights of oppressed nationalities. At a Carnegie Hall meeting of the FOIF, which took place just two days after the American declaration of war on Germany, he made an appeal to Congress to ‘take such action as will secure the independence of Ireland, not at the end of the war when scraps of paper may be safely torn up, but now when America’s intervention will count for more than at any time in the future.’ (New York Times, 9 April 1917).

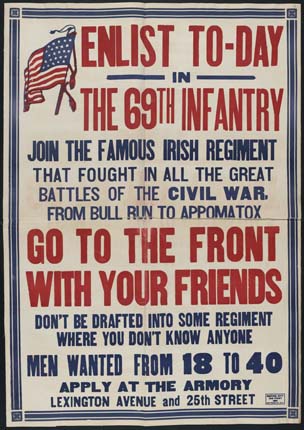

The Irish enlisted or were drafted into regiments throughout the United States, the New York-based ‘Fighting 69th’ became the most clearly identified Irish regiment and served with distinction on the Western Front. Once the war ended with an Allied victory in November 1918, the FOIF campaigned for American recognition for self-determination for Ireland and raised considerable funds for the Irish revolutionary cause.

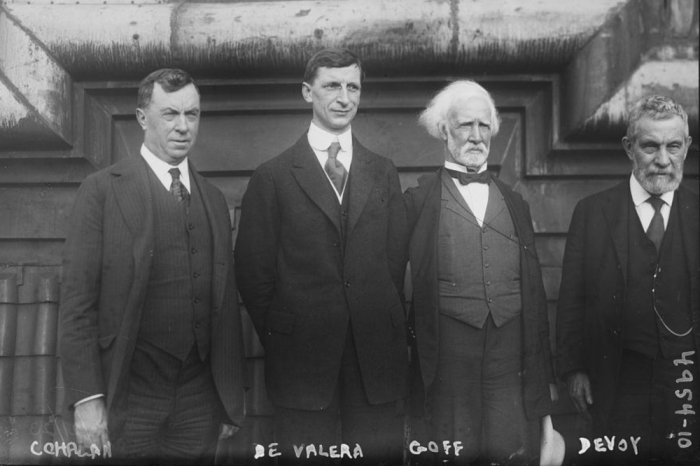

In June 1919, Éamon de Valera, President of the Irish Dáil (parliament), arrived in the United States. He remained there until November 1920. This seems a remarkably long absence for the leader of a nationalist movement then in the midst of a revolution. Yet he had good reasons for his mission. Like Irish leaders before him and since, he recognised the important role that Irish America could play in providing funds and diplomatic recognition for the Irish republican cause.

In achieving these objectives, de Valera expected to rely on the rapidly growing FOIF led by Daniel Cohalan. The FOIF, open to both men and women, had by the end of 1920, grown to 270,000 members organized in branches throughout the United States. However, de Valera’s relationship with Cohalan soon deteriorated. His famous remark about Cohalan: ‘Big as the country is, it was not big enough to hold the Judge and myself’, sums up the power struggle that developed between both men over tactics and strategy.

In spite of much infighting, de Valera finally returned to Ireland in December 1920, pleased with the outcome of his fund-raising mission. Over $5 million dollars had been raised, which far exceeded his expectations. However, he failed to obtain American recognition for an Irish Republic. While Wilson saw self-determination as a solution to the nationality problem of central Europe, he was not willing to advocate this principle to Ireland for fear of offending America’s wartime ally Great Britain.

Irish-American reaction to the war was complex and reveals the conflicting pressures upon Irish-America to both demonstrate their loyalty to the American nation and support the Irish nationalist cause in Ireland. Once the United States entered the war, the vast majority of Irish-American nationalists rallied behind the American flag and called for self-determination for Ireland in line with the President’s call for freedom for oppressed nationalities. However, Wilson did not have the Irish in mind when he made such calls and irrespective of the dispute between Cohalan and de Valera, American recognition of an Irish Republic was never obtainable.

Michael Dean: Indefatigable Irish-Minnesotan Singer and Songcatcher

Brian Miller

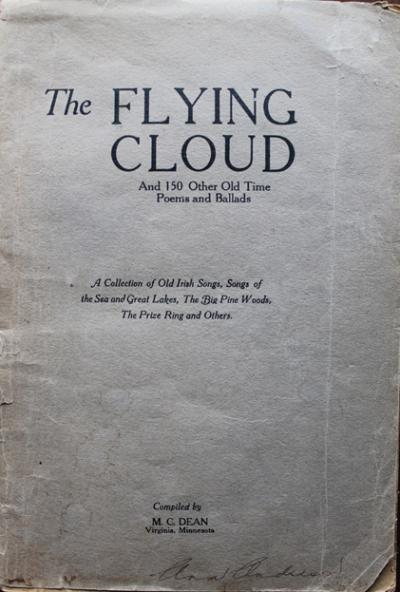

Michael Cassius Dean’s 1922 songster The Flying Cloud, published in Virginia, Minnesota in 1922, was the first significant book of songs popular in the lumber camp bunkhouses of the Upper Midwest. Dean himself was unique among most songcatchers in that he himself was a former lumberjack and a singer in the tradition he documented. In fact, a year after publishing The Flying Cloud, Dean played the role of source singer for collector Franz Rickaby who transcribed 27 of his songs and recorded background information supplied by Dean. We now know that Dean also met collector Robert Winslow Gordon who recorded Dean singing fragments of 33 songs in 1924.

I am interested in Dean because he was a Minnesotan and also because his life, repertoire and singing style exemplify the strong Irish influence in the “woods singing tradition” once common throughout the white pine belt stretching from the Canadian Maritimes to Minnesota. The Dean book, Rickaby transcriptions and Gordon recordings combine to give us an unusually full picture of Dean’s songs and singing. I have spent the last decade filling out the details of his life through census documents, newspapers and letters.

Michael Cassius Dean’s parents were from County Mayo, Ireland. Dean was born in 1858 near Canton, New York in the northern Adirondacks, the eighth of nine children. He learned at least three of his songs, “The Lady Leroy,” “Young Charlotte” and “Caroline of Edinburg Town” from his Irish mother who, he told Rickaby, sang such tragic ballads as lullabies. When asked about “The Lady Leroy,” Dean said that “all his folks sang it” so perhaps there were other singers in his family as well. By the age of 15, Dean was spending time in northern New York logging camps. He later recalled that the loggers he met there were “mainly French-Canadian” though the only singer he mentioned to Rickaby from this time period was the (presumably Irish) Barney Murphy.

In the late 1870s, around the time of his 20th birthday, Dean followed the logging industry westward to Michigan where he worked as a lumberjack, likely in the Manistee area, for several years. From Michigan, he continued westward to Pine County, Minnesota where he arrived around 1885 and, his obituary says, “worked in the woods and saw mills of Hinckley.” The 1885 Minnesota Territorial Census lists 28-year-old “Michael McDone” as a boarder at Hinckley’s Morrison Hotel, an establishment frequented by lumbermen and run by Scottish/Nova Scotian immigrant John Morrison and his Irish immigrant wife, Mary.

In Hinckley, Dean found himself among many first and second generation Irish-American businessmen with ties to logging, railroads and saloons. These included Thomas Brennan whose lumber mill was Hinckley’s chief employer and Thomas’s brother James who was a saloon owner and first president of incorporated Hinckley. The Brennans grew up in the same small town in County Kilkenny as the influential Bishop John Ireland of St. Paul. William O’Brien operated logging camps on the nearby Kettle River and would go on to be one of Minnesota’s most successful lumber barons with a mansion on Summit Avenue next to the governor’s mansion. Today a state park is named for him.

Dean, soon after arriving in Hinckley, stopped doing woods work and began a thirty year career working in north woods saloons and hotels. From 1885 to 1915, Dean tended bar for at least 14 different establishments, some of which he owned himself, including places in Hinckley, Sandstone, Willow River, Pine City, Moose Lake, St. Paul and Superior, Wisconsin.

Folklorist Robert Bethke who worked with lumbermen in Dean’s native New York state, notes that north woods barrooms often acted as an extension of lumbercamp bunkhouse singing culture. It is likely that thirsty woodsmen, and Dean himself, sang in at least some of his establishments. Dean’s saloons and hotels catered to lumberjacks that poured into these towns at Christmas and in the spring when released from their alcohol-free, live-in lumber camps. Things sometimes got out of hand to the point that Dean kept a revolver behind the bar and used it more than once to restore order. Dean was also well-loved for his wit and hospitality and is frequently referred to as a “genial landlord” in Pine County newspapers.

Though he never strayed far from the saloon business during these years, Dean did try his hand at farming as well. The Dean farmhouse east of Hinckley played host to midwinter parties such as this one described in the Hinckley Enterprise:

The surprise party last week at M. C. Dean’s, was a most enjoyable event. Three sled loads drove out to his farmhouse, and by the way he has one of the most convenient and finely appointed farmhouses in this section, reaching there at 8:30. The kitchen was cleared, the fiddle started and from then on feet were tripping the light fantastic in a very fantastic manner. The more staid, stayed upstairs and tried conclusions at the card tables, some to their sorrows. About midnight the tables were set and all enjoyed themselves to the utmost, feasting on the good things set forth. The party broke up and all returned to town in the small hours of the morning. All appreciated the kindly attentions shown and pronounce M. C. Dean’s the place to go for a good time.

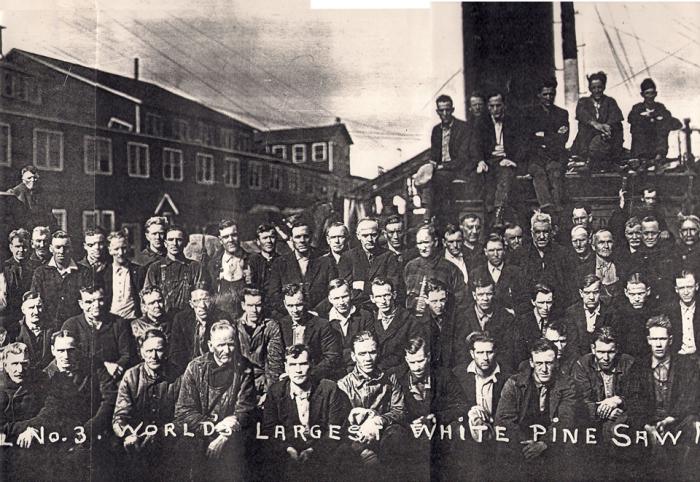

Around 1914, Dean retired from bartending and worked briefly on the Allouez ore docks in Superior, Wisconsin. Saloon keeping was becoming less viable as prohibition pressure and laws swept over Minnesota in the 1910s. Pine County voted itself dry in 1915. From the ore docks, Dean moved to Virginia, Minnesota where he took a job as night watchman for the Virginia and Rainy Lake Lumber Company’s enormous white pine lumber plant – the largest in the world at the time. He lived in the Pine Tree Inn, a boarding house across the street from the mill’s gate. After settling in at the Pine Tree Inn, in 1920, at the age of 62, Dean made his first visit in 31 years to his family back in Canton, New York.

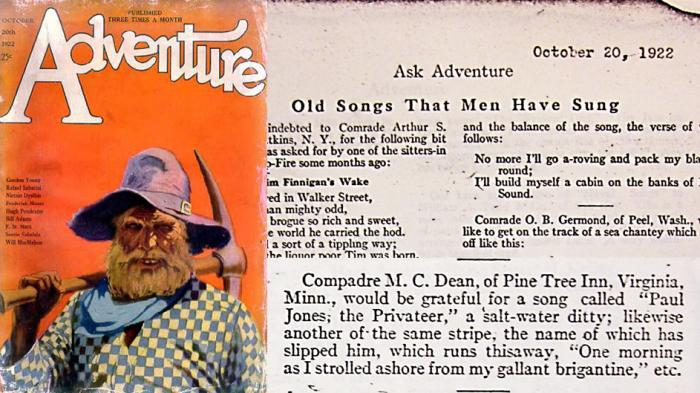

Perhaps this trip, combined with his return to outdoor laboring jobs at the ore docks and lumber mill, sparked a renewed interest in old songs. By 1922, Dean was writing in to the “Old Songs That Men Have Sung” column that ran in the pulp magazine Adventure asking for words to old sea songs he half remembered. He must have been at work before that at solidifying his repertoire before as that was the same year The Flying Cloud was published. Dean sent a copy of the new book to “Old Songs” editor Robert Frothingham with the following note:

I am sending you under separate cover a collection of old time songs that I have gathered up in my wandering around on the Lakes and in Lumber Camps and Rail Road Construction works there is not a song in the whole Book but what I have memorized and can repeat over=I will not say sing for I am not verry musical although I sing some times for my own amusement. People say I am easly amused.

The songster’s cover title gives an indication of the prominence of Irish songs in Dean’s repertoire: The Flying Cloud and 150 Other Old Time Poems and Ballads: A Collection of Old Irish Songs, Songs of the Sea and Great Lakes, The Big Pine Woods, The Prize Ring and Others.

The Flying Cloud contains 166 texts. About 100 contain Irish names or place names. Of those 100, about half are Irish street songs and half are Irish music hall songs – mainly from the American stage of the late 1800s. The street songs include songs of unrequited love, songs of Irish soldiers, Irish sailors, Irish patriots, Irish boxers, immigrant laments and several North American compositions about Irish railroad workers and other Irish laborers. Dean’s Irish music hall songs include compositions by Edward Harrigan, Joseph Skelly, Pat Rooney and several others. There are comic songs, sentimental songs longing for “The Land Where the Shamrocks Grow,” and songs of Irish-American political aspiration such as “Nothing’s Too Good for the Irish.” The remainder of the collection includes many minstrel and parlor songs, a few interesting popular songs about poor houses and poems on either side of the prohibition debate.

Interestingly, only five songs out of 166 are specifically about the experience of logging. When, years later, folklorist D.K. Wilgus declared Dean’s songster to be “a slice of the repertoire of the Northern folksinger” he was acknowledging the fact that lumber camp singing was only very seldom about lumbering.

It was likely the publication of The Flying Cloud that brought Dean to the attention of Grand Forks-based collector Franz Rickaby who visited Dean at the Pine Tree Inn in the summer of 1923. Rickaby called Dean “an indefatigable dispenser of good fellowship” and considered him among the class of woods singers possessing “the gifts of a naturally good voice, a particularly retentive memory, and an inherent inclination to sing.”

Meanwhile, Dean’s letters to “Old Songs That Men Have Sung” connected him to a network of other old tradition bearers (and the editors of the column itself) who corresponded with him, swapped songs and purchased copies of The Flying Cloud by mail order (for 75 cents). These relationships led to “Old Songs” editor Robert Winslow Gordon tracking Dean down at his sister’s house back in Canton, NY where, the local newspaper reported, “M.C. Dean…, who has a fine rich voice sung into the recording machine during the entire day.”

The Gordon recordings reveal Dean’s singing style to exhibit many characteristics of Irish traditional singing. He sings with a leisurely pace, often drawing out particular words for emphasis. Dean’s ornamentation is relatively subtle but he makes use of many grace notes and occasional melismatic flourishes. His tone is resonant and clear and he, like many Irish singers, often closes to a sustained sung “n” or “m” at the end of words. Though he was born in New York state, he also seems to have a bit of an Irish accent.

Michael Dean continued to correspond with other traditional singers by mail and to learn additional songs through his 70th birthday in 1928. By that time, academic collections of folk songs such as William R. MacKenzie’s Ballads and Sea Songs from Nova Scotia were citing The Flying Cloud as proof that a song was “found in Minnesota.” In August 1931, at the age of 72, Dean left the Virginia and Rainy Lake lumber mill and took a job as a laborer for St. Louis County. He was struck by a car and killed his first Monday on the job.

Brian Miller is the Director of the Celtic Junction Arts Center’s Eoin McKiernan Library. Brian was a 2014 recipient of the Parsons Fund Award from the American Folklife Center at the Library of Congress for his research into the history of Irish-influenced folk song in Minnesota. He writes the blog “Northwoods Songs” and has released two CDs of traditional songs from the Great Lakes region. He is also the creator of the Minnesota Folksong Collection website—a digital library of previously unpublished field recordings of northern Minnesotan singers (including Michael Dean) recorded in 1924.

The Home Place: Brian Friel’s Ireland

Anthony Roche (University College Dublin)

A lecture given at the University of St. Thomas, St. Paul, Minnesota, on Wednesday 26 April, 2017, for the Saint Paul Irish Arts Week, organised by Dr. Patrick O’Donnell.

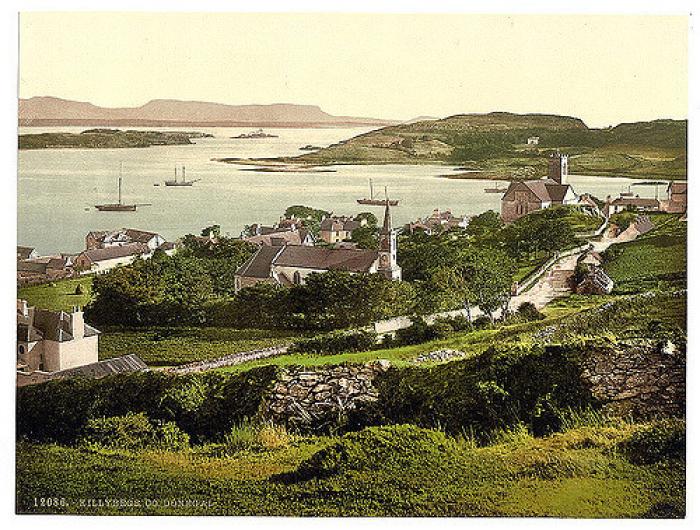

The great Irish playwright Brian Friel died on October 2015. The news was not unexpected – he was eighty-six years of age and had not been well for some time; but it still came as a great shock. When he died on October 3rd, the question arose as to where Brian Friel would be buried, as we waited on funeral arrangements. There were several unusual features about his funeral, and the location of his last resting place was among them. For most people, they would choose to be buried in their home place, where they had been born and raised. So Seamus Heaney was returned to Bellaghy, where there is an active cultural centre there, known as the Home Place, even though for many years Heaney had been living in Dublin and teaching at Harvard. Emigrants very often choose to be returned from the countries where they have lived most of their lives in order to be buried in Ireland. In Brian Friel’s case, he was born in Killyclogher, near Omagh, County Tyrone, and lived the first ten years there. But he chose not to be buried in Killyclogher. Tyrone is in Northern Ireland, a constituency to which Friel owed no emotional allegiance; his life and identity were complicated by that fact. In terms of his parents’ background, they both came from the same northwest area of the island which formed a natural hinterland and was closely bound together by family ties and local allegiances; Paddy Friel, his father, was a school teacher for many years in Omagh; his mother worked for the post office and was from Glenties in County Donegal. In 1922, seven years before Friel was born, the island of Ireland was divided in two by an act of mapmaking, as a border was drawn through Brian Friel’s home place. Friel never acknowledged the border and it is scarcely ever mentioned in the plays. In a 1970 interview with Des Rushe, he stated: ‘The Border has never been relevant to me. It has been an irritation, but I’ve never intellectually or emotionally accepted it.’ The new border bore most severely on Derry, creating a new name which nationalists could not bear to mention – Londonderry – and cutting off the city and its inhabitants from its natural hinterland, Donegal. The Friel family moved to Derry when Brian was ten and he lived there for many years, where like his father before him he worked as a teacher (of mathematics, as it happens). It is in Derry that his parents are buried; but it was not in Derry that Brian Friel chose to be buried. As the Northern Irish Troubles worsened, he moved his wife and four children to the Inishowen peninsula in Donegal, first to Muff (just over the border), then up to the top of the island in Greencastle, about as far north as you can go in Ireland. That was where Friel had been living for decades when he died, and yet he did not choose to be buried there either.

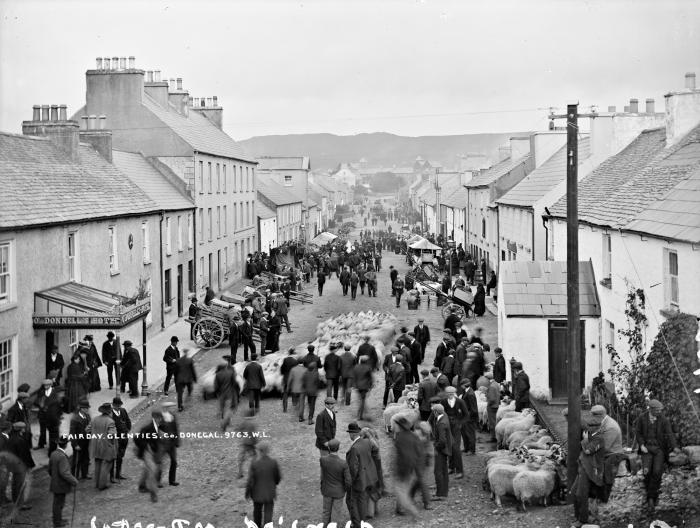

In the end, Brian Friel was buried in Glenties, much further south in the county, closer to Donegal town. This was the place where his mother had been born and raised. As he wrote in a 1972 prose piece entitled ‘Self-Portrait’: ‘When I was a boy we always spent a portion of our summer holidays in my mother’s old home near the village of Glenties in County Donegal. I have memories of those holidays that are as pellucid, as intense, as if they happened last week.’ When in November 2010 Brian Friel read the manuscript of my book, as he had to do in order to give permission for the many extracts from private letters, drafts and extracts from the plays, he did not make a single deletion (if he trusted you, he never interfered; if he didn’t he wouldn’t let you near his work with a bargepole). But he did make a biographical correction. I had referred to his mother as ‘Mary McLoone’ but he said her first name was ‘Christina’. In fact, his mother’s full name was Mary Christina McLoone; but clearly she favored the ‘Christina’. This information excited me because it provided even more evidence of just how autobiographical was Friel’s 1990 play, Dancing at Lughasa, where the mother of the narrator, Michael, is named Christina/Chrissie. The respectable Derry schoolteacher to whom Brian Friel’s real-life mother was married cuts a very different figure to the wandering Welsh playboy, Gerry Evans, who has fathered Michael in Lughnasa. But Christina Mundy and the four sisters by whom Michael is raised are closely based on ‘those five brave Glenties women’ to whom the printed version of the play is dedicated; they even have the same first names: Kate, Maggie, Agnes, Christina and Rose.

Family and friends gather at the burial ceremony of Brian Friel, at Glenties Cemetery, Co Donegal. Photograph: Dara Mac Donaill/The Irish Times

And so it was in his mother’s home place, Glenties, County Donegal, that Brian Friel chose to be buried on Sunday, October 5th, 2015. It would have some bearing that Glenties is in the Republic of Ireland rather than the North, but the primary consideration (as always with Friel) was the affective, emotional one. On that day the cortege left the Friel home in Greencastle for the long drive to Glenties, where the mourners had assembled. Most unusually, there was no church ceremony. Brian Friel was born and raised a Catholic Nationalist in Northern Ireland and, as shown by the diary he kept during his three-month sojourn in Minneapolis in 1963 (when he was thirty-four), Friel not only kept up regular Sunday mass attendance but also went to confession at least once and attended devotions. (His period in the Twin Citie in 1963 coincided with Easter.) Brian Friel had entered Maynooth in 1945 as a seminarian; but he graduated in 1948 without becoming a priest, claiming later that his paganism got in the way. He admitted in 1970 he was not as ‘intensely Catholic’ as he used to be. But a good many writers of whom this would have been the case (such as Seamus Heaney) still opt in the end for a full Catholic funeral. In Friel’s case, the hearse drove straight through Glenties to the cemetery. With no church service,the attendance of members of the general public was considerably reduced. At the graveside was a priest who recited several prayers, including (if memory serves) a decade of the rosary; thus that facet of Friel’s spiritual biography was acknowedged but did not predominate in the usual way. The poet Tom Paulin recited Heaney’s beautiful poem about his aunt, ‘Sunlight’; and fellow playwright Thomas Kilroy spoke of what the final curtain means in theatrical and human terms before closing with Prospero’s memorable lines in The Tempest, a play widely taken to be Shakespeare’s farewell to his art: ‘Our revels now are ended.These our actors […]/ Are melted into air, into thin air:/ And, like the baseless fabric of this vision,/ The cloud-capp’d towers, the gorgeous palaces,/ The solemn temples, the great globe itself,/ Yea, all which it inherit, shall dissolve,/ And, like this insubstantial pageant faded,/ Leave not a rack behind. We are such stuff/As dreams are made on; and our little life/Is rounded with a sleep.’ The choice of poem could not have been more apposite; since the sun shone throughout the day, even though it was October. (My wife got sunburned.) In Noel Pearson’s 2000 documentary on Friel, fellow playwright Frank McGuinness says that Friel writes as if Donegal were set in the Mediterranean, since in most of the plays the sun is always shining. Friel was not buried in the old graveyard in Glenties, which I visited in 2008 in the company of his cousin Casimir McGill who pointed out where the real-life equivalents of Kate and Maggie from Dancing at Lughnasa were buried. Also buried in the same Glenties cemetery was Father Barney MacLoone who like Father Jack in the play had contracted malaria on the missions in Africa and had come back to Glenties to die. When I asked Friel where his mother was buried, that’s when he told me she was in Derry with his father. The real-life equivalents of Agnes and Rose were missing, of course, because (as the play indicates in Michael’s monologue) they had emigrated to England and died there years later of poverty and destitution. In the seven years since I last visited, a new graveyard had opened in Glenties, about a mile outside the town and at the top of a steep hill. To that high promontory Brian Friel was brought in his wicker-basket and laid to rest, with a beautiful view down the valley. The scene at the funeral was like something from one of the plays. Friends gathered with his wife Anne and grown-up children Mary, Judy, Sally and David to mourn but also to remember and were reluctant to part because, as Kate says in the final scene of Lughnasa: ‘There’s still great heat in that sun’. But the written works remain and persist, an extraordinary legacy of fifty years as a writer.

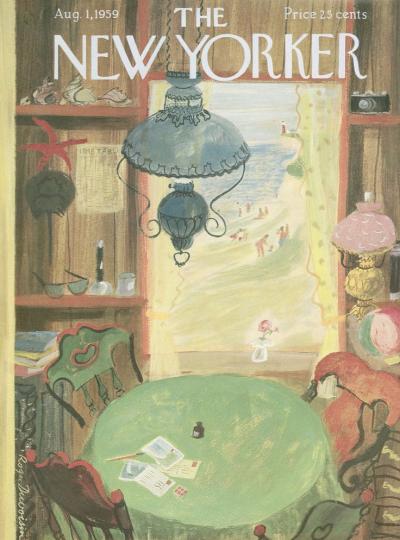

Brian Friel began his career in the 1950s by writing both short stories and plays, like his great Russian precursor, Anton Chekhov. His first short story was published in The Bell in 1951 but a huge breakthrough, both in financial and international terms, was the publication of his story ‘The Skelper’ in The New Yorker in 1959. Shortly thereafter, Friel signed a ‘First Read’ contract with The New Yorker. For a long time, I thought this meant a straightforward guarantee that all of Friel’s short stories would be published in The New Yorker before being gathered subsequently into book collections. It was not quite as straightforward as that. As the name of the arrangement suggests, The New Yorker got to read every story Friel wrote before anyone else and could then decide whether they wished to publish it or not. Friel’s correspondence in the 1960s with the editor Roger Angell shows that, while some stories were accepted, others were rejected; some of those stories were rejected outright while others allowed of revising and resubmission; the question then arose as to whether the author would agree to such a process and whether it would be successful. In all, between 1959 and 1965, Brian Friel published ten stories in The New Yorker, but three of these were appeared in 1960 and three more in 1961; in the remaining four years, he barely managed to place one story a year, though he still continued to submit stories to The New Yorker on a regular basis. These stories were subsequently gathered into two collections, The Saucer of Larks in 1962 and The Gold in the Sea in 1966. The New Yorker paid $1,750 per story, a considerable sum in the early 1960s. Buoyed by this success, Brian Friel in 1960 made the momentous decision to quit his teaching job in Derry and become a full-time writer; quite something for a young married man with a growing family to do.

Almost all of Friel’s short stories are set in Northern Ireland and most have a child protagonist, like the most famous short stories of his great Irish predecessor in the genre, Frank O’Connor. Memory is central to many of the short stories, as later in the plays. In ‘Among the Ruins’, one of the best, a father brings his family back to his home place in Donegal and tries to reanimate a treasured memory and draw his young son into sharing it. Because the emphasis in so many of Friel’s short stories is nostalgic and because so many of the protagonists are children or adults recalling their childhood, the political implications of the Northern Ireland setting are evaded. This is less the case in the plays. All three of Brian Friel’s radio plays of the 1950s and two of his first three stage plays are set in Northern Ireland. The other play, The Enemy Within, which was staged in Dublin at the Abbey Theatre in 1962, is about St. Columba and is set on the island of Iona off the coast of Scotland, where Columba founded a monastery with his monks; this is by far the most successful of the early plays and that fact is not unrelated to the choice of setting. The father in 1963’s The Blind Mice runs a public house in Northern Ireland and when a return celebration for his missionary son is planned, he is horrified because it will identify his pub as a Catholic house and drive away his Protestant customers. Whatever subject a playwright from Northern Ireland who sets his plays there may pursue, the sectarian issue is bound to emerge sooner or later and will swamp and overcome the play’s theme by drawing it in a predetermined direction.

With his breakthrough play, 1964’s Philadelphia, Here I Come, Friel chose instead to set one of his plays (for the very first time) in County Donegal in the Republic of Ireland. The play’s locale is called Ballybeg, which is a direct translation of the Gaelic phrase, baile beag, meaning ‘small town’. At a single stroke, Friel had removed his play and its setting from the politics of Northern Ireland; or rather he had placed them at one remove, which gave him greater artistic freedom in the handling of those politics. This was not a simple case of opting for the Republic of Ireland over the North, as might at first appear. For Donegal, as I indicated earlier when talking about Friel’s parents, is linked in many ways to the North, both geographically as the northernmost county in Ireland and as an integral part of the ancient province of Ulster, one of nine counties reduced to six when the border was set up and the country divided. Although constitutionally part of the Republic, Donegal is a great distance away from Dublin (as many of Friel’s works dramatise) and is physically separated to a considerable degree from the other twenty-five counties. Donegal may be seen to operate as a place apart from both jurisdictions, with Friel in his writings casting a wary eye on both constituencies ( and their shortcomings) and withholding his full allegiance from either.

Friel wrote Philadelphia, Here I Come! in 1963, the fourth of his stage plays but the first to achieve a dramatic breakthrough and to gather substantial acclaim and success, both in Ireland and internationally. This fact must be linked to a crucial sojourn Friel enjoyed in that same year when he spent several months in Minneapolis as an observer at the about-to-be-opened Guthrie Theatre. Since I am speaking tonight in the Twin Cities and because the time here was so crucial to Friel and his development, I would like to spend some time now on this visit, drawing on the various published writings and on a private diary Friel kept during his visit which is held in the Friel Papers at the National Library of Ireland. Friel’s visit came about as a result of an Arts Council grant and a direct invitation from Sir Tyrone Guthrie. Guthrie was born in Tunbridge Wells and was in many ways the quintessential Englishman: looking like a member of the British military with his height and his clipped moustache and his cut-glass accent. But Guthrie’s allegiances were complicated by a Scottish father and an Irish mother, as Friel pointed out in a piece he wrote for Holiday magazine in 1964 entitled ‘The Giant of Monaghan’: ‘there is [in him] that baffling combination of English reserve, Irish exuberance and Scottish astuteness.’ Friel’s article looks at the many faces of Tyrone Guthrie, the chameleon-like qualities that made him so suited to being a theatre director. But as his life and career progressed, Tyrone Guthrie came to insist more on his Irishness. By the early 1960s he had inherited (and he and his wife now lived in) his mother’s ancestral home in Ireland, Annaghmakerrig. As Friel describes it, Annaghamkerrig was ‘a huge rambling house overlooking a lake in a very remote and heavily wooded part of County Monaghan, Ireland’. Guthrie also regretted that he had not spent more time directing plays in Ireland (his lack of Gaelic ruled him out for the Abbey Theatre during Ernest Blythe’s lengthy tenure as manager). In particular he wished to encourage young Irish playwrights in his later years. Guthrie was one of the first and certainly the most important theatrical mentor in regard to Brian Friel’s potential as a playwright. First alerted to him by a story in The New Yorker, Guthrie wrote to Friel stressing their shared Northern Irish background. He attended a performance of The Enemy Within at the Abbey Theatre during the 1962 Dublin Theatre Festival and thought there was promise in what he saw. Hence the invitation to Friel to come to Minneapolis and sit in on rehearsals of the plays to be staged in the Guthrie’s first season: a modern-dress Hamlet and Chekhov’s Three Sisters, both directed by Guthrie, and Molière’s The Miser, directed by Douglas Campbell.

Friel later described his own situation as a budding playwright in 1963 as follows: ‘I found myself at thirty years of age embarked on a theatrical career almost totally ignorant of the mechanics of play-writing and play-production apart from an intuitive knowledge. […] So I packed my bags and with my wife and two children went to Minneapolis in Minnesota where a new theatre was being created by Tyrone Guthrie and there I lived for six months.’ This, from his ‘Self-Portrait’ of 1972, like the other accounts of the visit Friel has written, is inconsistent and somewhat contradictory. Did he write to Guthrie on his own initiative or was he the recipient of an invitation from the great man? Was he already working on his breakthrough play, Philadelphia, Here I Come!, or did he only sit down and write it after his return to Ireland? How long did he spend here, exactly? Periods of between three to six months have been suggested. During this time, Brian Friel was writing a weekly humorous column in The Irish Press and during these months that column was re-titled ‘American Diary’, ten of them altogether, covering his period here. But Friel also kept a private diary at the same time, which immediately discloses two inaccuracies in the account he gives in ‘Self-Portrait’. He was not attended on the entire trip by his wife, Anne, and his two young children, Paddy (who was seven) and Mary (who was five). Originally, it was intended that they all go and a family size apartment was booked in New York City for the first part of their stay. But the younger daughter Mary contracted chicken-pox and Anne put her foot down. Paddy was at risk and Anne Friel was not bringing two young daughters to a foreign country they had never visited before until Mary was better. So Brian Friel travelled on his own to New York on 25th March 1963. The diary mainly records the intense loneliness he felt over the following weeks there and in Minneapolis, where he flew almost a week later. So, on Saturday 30th March, he writes: ‘When Anne and the children join me the suspension will certainly snap and emotions will throb again.’ But that loneliness made Friel seek others out and talk to them, especially two of the actors staying at the Oak Grove apartments in Minneapolis, Ed Prebble and Paul Ballantyne. Most of this activity ceased after the family finally arrived in New York on Friday, 19th April, flying to the Twin Cities four days later.

The diary for the first time establishes a precise and accurate timeline for Friel’s Guthrie sojourn. He was in Minneapolis from 30th March until 17th June, a total of eighty days or almost twelve weeks (not six months, as was quoted earlier). Adding the time in New York at either end, Friel was ninety-four days or fourteen weeks in the U.S.A.- a three and a half month stay. On the one hand, as he wrote in ‘Self-Portrait’, it provided a necessary ‘parole from inbred, claustrophobic Ireland’ and conferred on him ‘a sense of liberation’ and ‘a necessary self-confidence’. On the other, as he confessed in the diary, ‘experience has taught me this: that I am no traveller. I enjoy neither journeying nor the sight of new places. Perhaps if Anne were here things would be different. On the credit side this experience will lay my American ghost. Perhaps I shall be back again; but if I am, I will not be wide-eyed nor so stupidly naive nor so poor.’ This was, however briefly, Friel’s first experience of exile. There is no sense in what he writes in ‘Self-Portrait’ that he desired a permanent exile from Ireland. Friel returned with his family to Ireland in June 1963, where he lived for the next fifty years building a worldwide career in theatre from the Northern fastnesses of Derry and Donegal. If Friel after the Minneapolis sojourn returned to live and work in Ireland, he did so as an inner emigré, a writer for whom the notion of home was elusive and the stance towards the society critical. What he gained from the time at the Guthrie was the possibility of a life in the theatre, of the theatre as providing a kind of home.

The diary also provides for the first time precise and accurate information on just how much and what of the Guthrie’s three opening productions Friel saw when he was here. When he arrived in Minneapolis at the start of April 1963, The Miser and Hamlet were in the early stages of rehearsal. Friel attended these rehearsals regularly and later saw both plays on stage before a live audience; but he did not accompany his wife to either of the opening nights, an anticipation of his avoidance of his own first nights when he became a more established playwright in his own right. He did, however, attend the opening of the Guthrie Theatre on Sunday May 5th and found it ‘very moving’. The rehearsals of The Miser yielded diminishing returns, since Friel writes of how Douglas Campbell drilled his actors to perform their scenes in a particular way and then got them to repeat what they had learned. Guthrie, by contrast, was creative and unpredictable, often improvising a new bit of business with a particular actor when he thought the energy of a scene was flagging. For a long time at a Guthrie rehearsal, it seemed as if very little was happening. Then, what Friel terms in ‘The Giant of Monaghan’ a ‘Guthrie-stride’ happened and the stage was transformed:

But then the hour of inspiration would come, lasting maybe twenty minutes, maybe five, and at those moments, […] Guthrie radiated his infectious excitement so that the actors caught it, responded to it, excited him in turn. Then, in those precious times of action and reaction, director and cast worked in such intimate communication, so intensely, so vibrantly, so fluidly, that the distinction between director and directed seemed to disappear […] so that the scene suddenly matured in meaning and significance and beauty…

In the light of his experience of the process of live theatre at the Guthrie, observing ‘the great man himself’ directing, Friel’s judgement on the three stage plays he had written and seen produced during the previous five years of his career was severe: ‘I made the startling and humiliating discovery that the few plays I had written were not the masterpieces I had thought them to be but were, in sad truth, tedious and tendentious and terribly boring.’ The play he was to produce after his time in Minneapolis was to be of a very different kind.

Friel’s assessment of those early plays is excessively severe; but the fact remains that, when Philadelphia, Here I Come! was premiered at the Dublin Theatre Festival in September 1964, the press coverage scarcely mentioned his three previous stage plays and concentrated instead on Friel’s reputation as a short story writer. As is clear, Friel spent much of his days in Minneapolis attending rehearsals. He was not only present during rehearsals of The Miser and Hamlet but from May 14 1963 of Chekhov’s Three Sisters, which Guthrie was also directing. Friel spent most of the evenings writing, not plays but short stories and articles. A play was clearly gestating. But the bulk of his writing and conscious career thoughts were devoted to the articles and short stories. On Monday April 22, while in New York to pick up the family, Friel met New Yorker editor Roger Angell for lunch. His diary records: ‘I like Roger more and more. He was very thoughtful and very anxious to discuss personal [mine] matters.’ Angell’s subsequent letter to Friel shows that their discussion centred around Friel’s career and the writer’s concerns about the stage he had reached. Angell’s advice is valuable and worth quoting; Friel obviously thought so because it is the only one of Angell’s letters from this period that he retained:

I do not share your glooms and despairs about your limitations as a writer.

I think, as I said, that you are only going through a complex process of self- discovery that is bound to occur when a writer has completed a first group of stories he finds within himself and that he writes mostly by instinct and out of sheer exuberance. I think you are now in the next phase, when writing is more calculated and more intelligent, and depends more on knowledge of one’s art. In other words, you are becoming a professional and you are learning the hazards and difficulties of your profession. I am quite certain that in the long run this knowledge will lead to greater self-confidence and to many fine stories.

Roger Angell’s perceptive analysis of Friel’s writing was accurate, so far as it went. Friel had completed a first group of short stories, written instinctively and spontaneously and drawing mostly on his childhood. He found it extremely difficulty, and lacked a sound basis, for moving into the necessary second phase identified by Angell. Friel spent much of the remaining time in Minneapolis writing a short story for The New Yorker entitled ‘The Flowers of Kiltymore’ which he then sent to Angell. On June 10th Friel records: ‘Got word from Roger Angell that he does not like “The Flowers of Kiltymore”’. Nor was Friel offered the possibility of a rewrite, as he usually was with the earlier, more spontaneous stories. That letter of rejection from Angell of ‘The Flowers of Kiltymore’ is not in the archive. In 1960 and 1961, Brian Friel published three stories per year in The New Yorker, a success which had obviously helped to inspire his decision to retire from teaching and become a full-time writer. In 1962, 1963, 1964 and 1965, he only published one story a year with them; a greater number was rejected. On 31 July 1965 The New Yorker published ‘The Gold in the Sea’ by Brian Friel. It became the title story of his second collection of short stories published in 1966. ‘The Gold in the Sea’ was the last Friel short story ever submitted to The New Yorker – and also the last short story Friel ever wrote. Roger Angell continued to write him intermittently, friendly letters mainly full of chat but always ending with a request for a new short story. On one occasion, Friel sent him one of the two one-act plays from his 1967 work for the stage, Lovers. Angell replied with a polite but firm letter turning it down, saying short stories not plays were what The New Yorker wanted from Brian Friel. In the same letter, Angell drew attention to the lines around the block in New York for Philadelphia, Here I Come!.

Although he continued to work on one or two short stories after Minneapolis (‘Everything Neat and Tidy’, for example,which was completed while at the Twin Cities in 1963 but not published in The New Yorker until November 1964), it is clear that Friel’s momentous decision not to write any more short stories – ever – crystallised during those three months. And having contributed a humorous newspaper column on a weekly basis first to The Irish Times and then, in 1962 and 1963, to The Irish Press, Friel’s column in the latter entitled ‘The Returned Yank’ published on Saturday August 10 1963 turned out to be the last such piece of humorous journalistic commentary Friel was ever to write. (Friel had submitted most of the ‘American Diaries’ to Angell for his consideration while still in the U.S.; they were returned.) Roger Angell had been correct, in one sense. After June 1963 Brian Friel was to enter a second phase of his writing. But he took what The New Yorker editor had said to him about the short story and instead applied the advice to his writing for the theatre. What Friel gained from his time of apprenticeship in Minneapolis was exactly what he had earlier lacked, a greater ‘knowledge of one’s art’, but of theatrical rather than fictional art. Because of and directly after his time in Minneapolis, Brian Friel became a professional in relation to his playwriting, adopting a more ‘calculated and more intelligent’ approach to the writing of plays for the theatre.

The evidence of all of this emerged with Philadelphia, Here I Come!, which was to establish Friel’s reputation as a major playwright in 1964 in Ireland and 1965 in New York. It should come as no great surprise to discover – as the key entry in his diary reveals – that the plan for Philadelphia emerged at the end of his stay in Minneapolis. On Saturday 8th June 1963, two days before his latest short story is rejected by The New Yorker, Friel writes in his diary:

Have been thinking of the new play. My man’s name is not Ger, but Gar, Garry, Gareth. Never once in the entire play does he look at his alter-ego, but the alter ego looks at him ALL the time with almost detachment. The Alter Ego is masked throughout. Should there be a series of flashbacks or should the story be told in chronological order? What are our characteristics? […] We must have Religion and we must have Politics. And we must have Love/Sex/Marriage. And Pride. And Gareth. And Nostalgia – yes, yes, yes, fighting through tears, being beaten back by loud laughter.

The Guthrie apprenticeship, therefore, may be seen to have had its primary impact in the theatrical solution Friel devises to represent the divided feelings of his protagonist, Gar O’Donnell, the twenty-five year old Donegal man on the eve of his emigration to the United States. Friel divides young Gar into two characters, a public and a private, to be played by two different actors. (The idea that Gar Private was to be masked was soon dropped, as a degree of theatrical stylisation too far.) The stage directions and the play itself make clear that Gar Public ‘is the Gar that people see, talk to, talk about’ – the one that would take the role, as it were, in a naturalistic play, displaying different facets of his character to the various other people he encounters: mute and uncommunicative with his father, affectionate and joshing with the housekeeper Madge, defensive with his former girlfriend Kate and rather edgy as he gets ready to leave his former companions. Private Gar is an original creation that transforms the nature of the play, rendering it both more psychologically acute and more self-consciously theatrical. ‘Private Gar is the unseen man, the man within, the conscience, the alter ego, the secret thoughts, the id.’ (89) The double relationship between the two Gars is crucial to the success of the whole play, the dynamism on which it runs, ventilating and giving light, color, humor and a variety of perspectives to the human dilemma at its core, freeing the representation of that dilemma from an archaic, no longer adequate form.

The question which has always puzzled critics is: where did Friel get the idea of the double Gar from? It is almost certainly his innovation and the one or two precdecessors that have been mentioned (such as Lennox Robinson’s Church Street) seem unlikely. Both Patrick O’Donnell and I are convinced that a major source for this theatricalisation of the male lead, and in particular for the creation of Private Gar, came from Friel’s experience of watching Tyrone Guthrie direct two classic plays over the course of many weeks of rehearsal in the Guthrie Theater. Rereading Philadelphia, Here I Come! in the light of Friel’s detailed descriptions of Guthrie in rehearsal, it is difficult not to see some resemblance between that figure’s behavior in the theatre and the representation of Private Gar in Friel’s play. Like Guthrie, Private Gar is an extemely restless presence onstage, working on Public Gar when he threatens to become immobile and introspective. Private Gar has a freedom of movement, the power to move freely around the stage while Public Gar and the other ‘realistic’ characters in the play are bound to the prescribed rituals of their everyday dialogue and routines. Private questions them on what they are saying and the motives behind their actions. He clicks his fingers and claps his hands. He insists that momentum must be maintained, warns that silence is the enemy. But he also works to uncover the emotions at work beneath, particularly in relation to the uncommunicative father, taxing him with a key memory of Gar’s childhood when the family are saying a decade of the rosary. The figure of Gar Private resembles nothing so much as Tyrone Guthrie in rehearsal with his actors, insisting that the play must be kept entertaining.

Friel had hoped Guthrie would direct Philadelphia’s premiere production. He ends his article on ‘The Giant of Monaghan’ with a direct pitch, declaring his confidence that the acclaimed director of classic theatre would take on a contemporary work if ‘within the next decade some dramatist in some remote country [were to] write a play that throbbed with love and fun and sorrow and joy – and with a dash of horseplay thrown in for good measure’. But when asked to take on the assignment, Guthrie said he could not do so, that his schedule in Minneapolis prevented his taking on this production of Friel’s play in Dublin, however tempting. I suspect also that it was a question of which theater maker was to be given chief credit for the production. In the case of a classic play, the major credit went to the director and the innovative approach he or she adopted towards a work from the repertoire: hence, Guthrie’s Hamlet in Minneapolis in a modern-dress production. The credit for a new play would always go to the dramatist: hence, Brian Friel’s Philadelphia, Here I Come!. In a letter of October 3 1963, Guthrie sent Friel an extremely positive reading of the script. Ironically, the one feature of the play about which he expressed reservations was its double act: ‘Now for it: I can’t decide whether the dodge of having two actors play Private and Public, Ego and Alter Ego, is justified. I guess it ought to be tried.’ On the eve of opening night in September 1964 at the Gaiety Theatre in Dublin, the two actors playing the leads expressed similar doubts about whether the double act would work theatrically and be accepted and understood by the audience. The answer to their doubts from the play’s director, the Gate Theatre’s Hilton Edwards, memorably, was: ‘If you believe it so will they.’ When I spoke about the play in December 2016 in Dublin’s Little Museum, present at my talk was a brother of the actor who played Private Gar in that original 1964 production, Donal Donnelly. Maurice Donnelly said the audience bought into it and understood the double act right from the start.

I would like in the time remaining to briefly consider the complex issue of ‘home’ in relation to a number of key Friel plays from throughout his career. Philadelphia, Here I Come!, as I said earlier, is the first to be set in Ballybeg, Friel’s archeypal small town in County Donegal. Though not all of Friel’s plays are set there – 1973’s The Freedom of the City, which presents a version of the Bloody Sunday killings, is set in Derry – a good many of them are. It is interesting to note that many of the plays set in Ballybeg have been among the most successful of Friel’s career. This has something to do with the fact that all of those plays focus their consideration of Irish politics (‘and we must have Politics’) on the family, channeling that topic through the intense interactions of the members of one particular family. This is certainly the case with the first, Philadelphia, Here I Come! The household of S.B. O’Donnell remains the setting throughout. It is a lonely place, with only the one son and without the consoling presence of a mother. The housekeeper Madge is the mother surrogate (one of several in the play) who works to improve relations between father and son. I have written that there is always ‘in Friel’s small communities a sense of some lost or missing dimension, a context which would give meaning to the isolated and frequently despairing lives of his characters. Yet the plays are also filled with sun, with laughter, with music, with fun. It is this combination in Friel, of a surface gaiety compensating for a great deprivation which can scarcely be named or discussed, which gives his plays their characteristic tone.’ That missing dimension is often, as here, the absence of the mother and everything she represents in terms of feeling. Without her, the relationship between father and son much more resembles that between employer and employee, with their short, infrequent conversations in the play having to do with dry and banal business matters rather than with the fact that Gar is leaving in the morning for Philadelphia. Three times in the course of the play, Gar tries to construct a ‘home’ in which he might live. The first is when he struggles to evoke the missing mother, to summon her ghost. To do this, he relies on the oral testimony of the housekeeper, since his father never mentions or discusses his dead wife: ‘She was small, Madge says, and wild, and young, Madge says, from a place called Bailtefree beyond the mountains.’ (p. 102) The image is created of a beautiful, young woman, free and spirited, who married a man three times her age, who endured a year of sadness isolated in the house, and who died days after her one and only child was born. Gar’s second attempt at conjuring up his mother is perfromed through the one remaining sister, Aunt Lizzie, who has emigrated to the U.S. years earlier. On her return visit to Ballybeg the previous summer, Lizzie recalls: ‘And Mother, poor Mother, may God be good to her, she thought that just because Maire got this guy with a big store [she’s referring to S.B.] we should all of got guys with big stores.’ (p. 132) Friel’s ear had been sharpened in relation to Irish-American speech through his three months in NewYork and Minneapolis; and the returned Yank was to feature in the next two plays he wrote. Aunt Lizzie is summoned into presence through the flashback to the previous summer when the returned Yanks came back to Ballybeg to persuade Gar to emigrate to the U.S. and join them in Philadelphia as a surrogate son. Even though Gar Private is quick to point out Lizzie’s brash vulgarity, Gar Public is drawn to her because of her warmth and ready emotionalism in place of the cold restraint of his father; and he agrees to go. At play’s end, Gar tries to construct a sense of home by facing his father and drawing him into a personal conversation. But S.B. fails to remember the cherished childhood memory Gar has of being in a blue boat with his father. Private exits to the refuge of his bedroom to the jeering laughter of Private, his heart set on Philadelphia in the morning.

The figure and the speech of the returned Yank are more central to the next play, 1966’s The Loves of Cass McGuire. This is in many ways a sequel to Philadelphia, Here I Come!. Where the twenty-five year old Gar O’Donnell emigrates from Ballybeg to the USA, the seventy-year old Cass McGuire returns home to Ireland after fifty years in New York. The dates of her departure and return are politically resonant: she has left in 1916 and returns in 1966, the year in which the fiftieth anniversary of the Easter Rising was being commemorated. Cass returns to the ‘new Ireland’ of the 1960s which is enjoying the first flush of material prosperity. This precursor of ‘Celtic Tiger’ Ireland is represented through the figure and family of Cass’s brother, Harry McGuire, a successful businessman, whose four children have all trained for the professions. The family relative they welcome home shocks their bourgeois notions. Cass is verbally coarse, physically raucous, smokes incessantly and is frequently drunk. She speaks a brash, vital New York-ese acquired in the fifty years she spent working in a busy hash-house. Cass has some bawdy set-pieces she likes to perform and, far from being euphemistic about natural functions, takes care to stress all of the syllables in ‘ur-eye-nal’ when she drops it into the conversation. The references she makes to Jeff Olson, the man with whom she lived, makes it clear that their maiden aunt is anything but. It is her partner’s death that has precipitated Cass’s return to Ireland. But that Ireland, as represented by her upwardly mobile brother and his bourgeois family, has great difficulty in accommodating the unruly presence of Cass McGuire. We learn in the opening scene of her drunken night on the town, which Harry has covered up by paying for the breakages and ‘squaring’ things with the local police. Plans soon emerge for the old woman to be installed in a home, ironically entitled ‘Eden House’, which Cass repeatedly refers to as ‘the workhouse’ because the ‘home’ has been built on the site of one. Cass returns from one form of exile to another, to inner exile in an Ireland that in no way lives up to what she had imagined. Fintan O’Toole argues that the play ‘betrays an underlying uncertainty about whether or not its overwhelming sense of homelessness is caused by emigration.’ But as the philosopher Theodor Adorno has put it: ‘it is part of morality not to be at home in one’s home.’ The point is beautifully made when Harry visits his sister in Eden House on Christmas Day, and reveals that none of their three adult children is returning home for the holiday and that none of them is as successful as their parents have been pretending. Harry ends his confession to Cass by saying he wishes he could stay with his sister in the institutional home to which she has been confined rather than returning to the physical comforts and supposed consolations of the dream home he has constructed for his wife and family.

The more overtly political plays Friel wrote in the 1970s do not have to do with family and are not set in Ballybeg – The Freedom of the City takes place in Derry, as I said earlier, and Volunteers has a group of republican internees excavating the remains of a Viking settlement in Dublin. But in the late 1970s, in Living Quarters and Aristocrats, Friel returned to focus even more obessively on Ballybeg and the family. I will concentrate my remarks on Aristocrats since it is the better known and more accomplished of the two plays. Friel also returns to the dysfunctional father-son relationship in both plays. In Aristocrats, the father remains offstage for much of the play. District Justice O’Donnell is bed-ridden, dying, and so is confined to upstairs in the house for most of the action. In the play’s opening scene, a local handyman instals a baby-alarm on the downstairs wall so that any member of the family can respond to their father’s requests and needs. The device serves througout the play more as a loudspeaker to issue their father’s commands, to broadcast publicly the most intimate exchanges. Most surrealistically of all, the judge in his delirium addresses people who are present as if they were not there and speaks from his family bed as if from his judge’s bench, condemning the members of his family – sentencing them – for what he sees as their various betrayals and transgressions. In his father’s physical absence, the thirty-something son Casimir is free to roam the garden and to tell increasingly implausible anecdotes to a visiting American academic about the O’Donnell family’s association with great historical and cultural figures over the decades. The nervous, fussy Casimir seems less free than driven by inner demons, and nowhere is this more graphically or dramatically presented than in the closing moments of Act One. Casimir is bringing a carefully prepared lunch onto the lawn and the baby alarm suddenly erupts into life: ‘”Casimir!”’ At the sound of his father’s voice, Casimir jumps to attention, ‘rigid, terrified’ (p. 306), and sinks to the ground with the tray, weeping and terrified. This negative transformation wrought by the appearance of the father on the son is on a grander, more operatic scale than any which befalls Gar in Philadelphia. Casimir may be in his mid-thirties, with a wife and two children back in Hamburg, but his atrophied emotional life continues to centre itself in Ballybeg Hall.

What most seriously complicates and challenges the father-son relationship in Aristocrats, in both theatrical and gender terms, is the presence of three sisters. The reference alone cannot but signal a Chekhovian reference and resonance. Fifteen years after sitting in for weeks on Tyrone Guthrie’s direction of Chekhov’s Three Sisters in Minneapolis, Friel was writing his own version of Chekhov’s play for later staging by the Field Day Theatre Company he co-founded with the actor Stephen Rea. But it is in his original plays Living Quarters and Aristocrats, both of which add three sisters to the father-son relationship, that he makes the most creative play with Anton Chekhov. In Aristocrats, Judith, the eldest, runs Ballybeg Hall, having the care both of her ailing father and a sister who suffers from manic depression. For much of the first act she remains offstage; but her voice is also broadcast over the baby-alarm. She has to cope not only with her father’s physical needs but also manage his non-recognition and his accusations, as he bellows at her: ‘I can tell you confidentially – Judith betrayed us. […] Great betrayal; enormous betrayal.’ (p. 317) Judith’s entrance onstage at the end of the act is timed to witness Casimir’s breakdown and to ‘rock him in her arms as if he were a baby.’ (p. 307) This image of thwarted maternity has a context. Judith’s’great betrayal’ has consisted of going over the border to engage on the Catholic nationalist side in the Battle of the Bogside and in having a child through an affair with a Dutch reporter. That political and sexual act cannot be acknowledged in Ballybeg Hall, and so Judith has put her child up for adoption.The youngest sister, Claire, is also offstage for much of the first act. But her presence registers strongly through her offstage piano playing of Chopin. Casimir suggests that their father has strongly opposed Claire’s wish to become a concert performer, and so she has been forced to keep her performing to the private family stage rather than the public platform. Claire is the double of her absent and long-dead mother, who also suffered from a nervous condition and had been transferred by her husband immediately they married from her profession as an actress to a wife and mother in the private sphere. Alice is the sister most continuously onstage throughout the three acts. She stalks the limits of the stage, freed up from the physical restraint inhibiting her siblings by her drinking and also freed up vocally to tell some home truths concerning the O’Donnell family (the heavy drinkers in Friel are always the truth-tellers).

By the time we get to Dancing in Lughnasa in 1990, the women now occupy centre-stage and the men have been moved to the margins. The play is Friel’s most autobiographical, as I mentioned earlier; his own mother had the same first name as the mother in the play, Christina; and she too had four sisters with the same first names: Kate, Maggie, Agnes and Rose. The play is not entirely biographical: the narrator Michael’s father is not a respectable Derry schoolteacher to whom his mother is married but a wandering Welsh playboy and travelling salesman, Gerry Evans. When he visits Ballybeg and the five sisters twice in the course of the summer of 1936, when the play is set, Gerry dances with Christina and impulsively proposes to her: ‘Marry me, Chrissie. […] Will you marry me when I come back in two weeks? CHRIS: I don’t think so, Gerry. […] you’d walk out on me again. You wouldn’t intend to but that’s what would happen because that’s your nature and you can’t help yourself.’ It would also be an act of bigamy, since Michael reveals later in the play that after the war he got a letter telling him not only that Gerry Evans had died but that he had left a wife and a son called Michael behind him in Wales. The conventional and socially respectable response to Gerry’s proposal of marriage would have been for Christina to accept a marriage proposal from the father of her child. Instead, Chris lovingly but firmly turns him down, recognizing that Gerry would walk out on her again.

The one major change from his autobiography is for Friel to make Michael ‘illegitimate’, as it was called then. Christina’s decision to have a child ‘out of wedlock’ is followed up by her electing to keep the child and raise it as her own rather than putting him up for adoption. In this, she is supported by her sisters, including (it should be noted) the respectable and sensible eldest, Kate. Women teachers who had children in such circumstances were still being dismissed from employment in Irish Catholic schools into the 1970s. As Helen Lojek notes: ‘the sisters do not abandon Michael to an institution.’ In the course of the play Kate is dismissed from the teaching position on which the whole household depends because the local parish priest claims the numbers are falling. Kate flatly denies this is the case. Michael surmises that his uncle Jack is to blame. Jack is the other ‘father’ in Dancing at Lughnasa, a Catholic priest who went out to the missions in Africa to convert but who ends up being converted. Jack has come home to his sisters in Ballybeg, as it turns out, to die. Kate is shocked by the extent to which her beloved brother has ‘dabbled in joyous paganism’, to use Friel’s phrase in the notes for the play. As Michael reveals, ‘each new anecdote contained more revelations. And each new revelation startled – shocked – stunned – poor Aunt Kate. Until finally she hit on a phrase that appeased her: “his own distinctive search”. “Leaping around a fire and offering a little hen to Uka or Ito or whoever is not religion as I was taught it and indeed know it. […] But then Jack must make his own distinctive spiritual search”’ (p. 499). Michael surmises that the rogue priest may be responsible for Kate’s being fired; but a far likelier cause is the schoolteacher Kate Mundy continuing to love and cherish her ‘illegitimate’ nephew and to educate him in her school as well as at home.

Dancing at Lughnasa is set in 1936. In 1937, the then Taoiseach [Prime Minister] Eamon de Valera framed a Constitution for Ireland in close consultation with the Catholic Church. That document addressed precisely one sentence to women, identifying woman’s proper place as in “the home”: “the state recognizes that, by her life within the home, woman gives to the state a support without which the common good cannot be achieved.” The Ireland of the 1930s has long been a byword for conservatism, particularly in the area of gender politics. It is tragically ironic that such a political position should derive from the former Republican revolutionaries who promised a transformed society. The most betrayed character in this regard is Kate. She is critical of the period during World War One which her brother Jack spent as chaplain to the British Army in East Africa because, as Michael reveals, ‘Aunt Kate had been involved locally in the War of Independence’ (p. 436). This identifies Kte as a supporter of de Valera in his revolutionary phase but also indicates why she has continued that allegiance now that he has come to legitimate power. Kate’s defence of the Ireland of the 1930s requires her to adopt the following positions: to condemn Father Jack’s heterodox beliefs; to oppose Gerry Evans’ decision to go off and fight on the socialist side in the Spanish Civil War; and above all to forbid her sisters from going to the harvest dance. In doing all of this, Kate is betraying her own deeply held Republican beliefs. From the point of view of the women, the Irish Revolution that the Irish males claimed had been achieved was deeply flawed and far from complete. Pent up in the cottage throughout the play, their ‘life within the home’, the suppressed energies of the five Mundy sisters finally find an outlet in their wild, abandoned dance.

I would like to close with a brief word on Friel’s final original play, which has the same title as my talk, The Home Place. This 2005 work is directly informed by the figure of Tyrone Guthrie in its representation of an Anglo-Irish landlord at the time of the 1880s Land War. What seals the connection is Friel’s bestowing on Christopher Gore the catch-phrase that all those who attended Guthrie’s rehearsals remember. As Michael Blakemore describes it from an actor’s perspective: ‘If an actor didn’t give of his best he was in trouble and there could be no excuses. “Rise above it!” was Guthrie’s famous injunction to anyone who came to him worried, depressed or just plain ill.’ This advice, which Guthrie directed to others, must have been applied with no less force to himself; the apparent aimlessness is countered by the iron self-discipline, as Friel’s account of the director at work in Minneapolis fully recognizes. In The Home Place Christopher Gore initially applies his oft-repeated phrase, ‘Rise above’, to himself, as a family legacy handed down with the estate: ‘Rise above, Father always said – rise above – rise above.’ The phrase is implicitly extended to all those who have come from England to Ireland over the centuries as planters and who, no matter how many generations they remain, will always be regarded by the native population as non-Irish, as outsiders. Christopher comes to this recognition in a speech late in the play:

I’ll rise above. The planter has to be resilient, hasn’t he? No home, no country, a life of isolation and resentment. So he has to… resile. […] And that resentment will stalk him […] down through the next generation and the next and the next. The doomed nexus of those who believe themselves the possessors and those who believe they’re dispossessed. (p. 277)

The phrase in the play’s title, ‘the home place’, is referred by Christoper Gore, not to the Ballybeg estate on which he and his family have lived for generations, but to the place in England from which they have originated and to which they return every summer: ‘All those memories of Kent – they almost made me homesick.’ (p. 271) Friel has precisely inverted the relationship between Guthrie (who was born in Tunbridge Wells in Kent) and his home place. Where the young Tyrone Guthrie was brought back every summer to the Irish Big House of Annaghmakerrig for his roots to be renewed, Christopher Gore was sent in the opposite direction. Gore’s allegiances remain ambivalent and shifting between Ireland and England and which country may properly be regarded as the truer ‘home place’. Mike Wilcock wonders whether differences between the native Irish playwright Brian Friel and the Anglo-Irish director Sir Tyrone Guthrie might have been lessened because they first met in the neutral shared ground of the USA and that their differences would have registered with more force on home ground. Though both were Irishmen with a strong streak in them of the rebel, they came ‘from different sides of the Irish cultural divide’: Catholic nationalist and Protestant planter. In this regard, Friel’s most fascinating weekly ‘American Diary’ in The Irish Press in 1963 describes his seeing the following headline on a Boston Irish-American newspaper while in New York: ‘”Brookeborough Resigns”’. The headline refers to the then Unionist Prime Minister of Northern Ireland, Basil Brookeborough. As Friel writes: